Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Woman Wonder: The U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame Recognizes Stowe Adventurer Jan Reynolds

Published March 15, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated April 10, 2023 at 11:53 a.m.

Or perhaps she's a composite, bits of several people rolled into one. World-class biathlon competitor. Holder of the high-altitude skiing record for women. First woman to circumnavigate Mount Everest on skis. Part of the first attempt to fly over Everest in a hot-air balloon. Successful writer-photographer of children's books about the lives of the world's Indigenous peoples.

Maybe she's a folk hero. You know, like Paula Bunyan.

Yet here she sits in a Winooski diner, all five feet, eight inches and 135 pounds of her. Janet Louise Reynolds, known to other adventurers as "Janbo" and "Indiana Jan." A feat-seeking missile of athleticism and achievement. One is tempted to ask her for ID — the card that says "legendary sports action figure."

Some folks regard Reynolds, an eighth-generation Vermonter, as larger than life. But she is life itself, with a done-that list too big for any bucket.

"She's an original," said Perry Bland, who was her Nordic skiing coach at the University of Vermont in the mid-1970s. "There's no one like her."

Later this month, on March 24, Reynolds will leave her Stowe aerie on Mountain Road and travel to Big Sky, Mont., to be inducted into the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame.

Her nomination, submitted by Hall of Fame member and extreme skier Kristen Ulmer reads, in part: "Jan became the first athlete to be hired as a professional by The North Face, as a skier and mountaineer. This not only shattered the glass ceiling, it set the stage for countless athletes for decades to come ... Current extreme mountain skiers, male and female, stand on Jan's shoulders."

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Bruce Benedict/Jan Reynolds

- Jan Reynolds shooting a .22 rifle in biathlon competition

Others supporting her nomination include Vermont Olympic gold medalist Barbara Ann Cochran, TV journalist Dr. Bob Arnot and cross-country skier John Caldwell of Putney. Reynolds will join 20 other Vermonters in the national Hall of Fame, including Alpine skiing champions Suzy Chaffee and Marilyn Cochran Brown, cross-country skier Bill Koch, Mt. Mansfield Company founder Sepp Ruschp, and snowboard pioneer Jake Burton Carpenter.

Reynolds has traveled to the farthest reaches of the globe and authored 20 books (so far). And yet she is largely unrecognized by all but the cognoscenti, her accomplishments consigned to the attic of America's memory. Why?

In her heyday, "Women just weren't recognized as being important athletes compared to men," said the North Face founder Kenneth "Hap" Klopp, who recognized Reynolds as extraordinary. "It had to do with the chauvinistic attitude of people regarding sports."

Reynolds still has the air — and appetite — of an antsy teenager. Working her way through eggs Benedict, toast and home fries, she talked nonstop, pausing occasionally to pull out a map or some other document. Our waiter stared; she looked familiar, but he couldn't place her. "I'm a woodchuck," she grinned, leaning back in her regulation flannel shirt and down vest.

Now nearly 67, Reynolds said she long ago decided to play the cards she was dealt. "In all my expeditions, I never really focused on the sexism," she said. "I accepted that my male climbing partners never had to prove it again after doing it once. But every single time I'm on another expedition with men I've never climbed with before, I've got to prove it again."

And so she did, again and again.

'You Got Yourself a Racehorse"

Reynolds grew up on a dairy farm in Middlebury, the sixth child in a gaggle of seven. One day she rode with her dad to see a man who fixed farm vehicles.

"I was about 5 years old, and my dad and Leonard were talking and laughing, cracking beers, just having a great time," she recalled. "When I went with my mom to visit other moms, they were always like, 'Oh, God, I gotta do this, and I gotta do that.'

"I decided I wanted what my dad had," she said. "I wanted to have fun."

Reynolds' role model was from children's books: Pippi Longstocking, the fictional pigtailed Swedish 9-year-old with superhuman powers for whom "everything was possible." Among her siblings, Jan was the one who never put away her sneakers, never gave up outdoors play.

"She was the outlier," said Ashley Wolff of Leicester, who has known Reynolds since fourth grade. "None of the other [siblings] had the wanderlust or striving for excellence in athletics."

Wolff said Reynolds' dad provided unintentional motivation: "He opposed almost everything Jan wanted to do, and he probably drove her to prove she could."

At Middlebury Union High School, Reynolds was part of a team that won the state cross-country ski championships twice in the early '70s. At the University of Vermont, her team won the NCAA championship in 1978.

While she was at UVM, women's Nordic coach Bland took his talented team out to New Mexico to train and compete in a meet or two. Following one tough competition, Bland was driving the rental car when he heard panicked voices from the rear: "It's Jan, she's not breathing!" Bland stopped the car, got out and looked in at Reynolds as she suddenly resumed normal respiration.

"It was scary," the coach recalled. "She'd skied hard — she had the mental toughness to kill herself. I said to myself, You got yourself a racehorse here."

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Dimitar Dimitrov/Jan Reynolds

- Jan Reynolds skinning up the Rila Mountains in Bulgaria

Nancy Dickson Gaudreau, who was her teammate and friend in both high school and college, said Reynolds "was kind of fearless and adventurous ... confident and very strong and determined out in the racecourse. Other people had those qualities, but she really had them in spades."

After graduating from UVM in 1978, Reynolds left sea-level activities behind and set out to climb and ski higher, faster, longer than anyone. She became the training and expedition partner of her boyfriend, adventurer Ned Gillette of Barre. Together they completed the first free-heel ski and climbing traverse of New Zealand's Southern Alps — the beginning of many first-ever expeditions she and Gillette embarked on over the next decade. Between trips, Reynolds worked at the Trapp Family Lodge in Stowe as a ski instructor to support her high-peaks habit.

In 1980, Reynolds set the women's world record for high-altitude skiing when she descended 24,757-foot Mount Muztagh Ata in China. The following year, Reynolds and Gillette spent 120 days skiing, climbing and hiking to complete the first-ever 300-mile Everest Grand Circle circumnavigation.

"I don't think anyone really realized if I had been a man doing all the things I was doing, there would be people tracking me — and sponsors," Reynolds said.

Needing a break from mountaineering, Reynolds joined the U.S. Biathlon team, which took third place in the relay at the 1984 World Championships in Chamonix, France. It is the only Olympic Winter Games event that requires two different skills: skiing and marksmanship. One commentator likened it to running up 10 flights of stairs, then trying to thread a needle.

Above Everest, in a Balloon

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Jan Reynolds

- Jan Reynolds in a hot-air balloon approaching Mount Everest (right)

That year, 1984, also saw the first in a bizarre series of events that led Reynolds to one of her wildest — and most dangerous — exploits. As she recounted in her 2019 book, The Glass Summit: One Woman's Epic Journey Breaking Through, it came about like this.

Reynolds and Gillette had stopped in London so that he could pitch a film company on a plan to row a boat to Antarctica from the tip of South America. Reynolds was not interested, so she waited in an anteroom. A friendly secretary asked if Reynolds needed anything and was soon mesmerized by the visitor's account of some of her exploits, particularly her circumnavigation of Mount Everest.

The next day, executives from Orana Films, an Australian company specializing in adventure documentaries, met in the same offices to discuss filming an attempt to fly a hot-air balloon over Everest. The joint British-Australian project desperately needed the American market to get sufficient financing, and the only way to do that was to put a Yank in the basket — preferably a woman, since the rest of the crew were men.

"So," one of the execs said ruefully, "all we need is an American woman skilled in high altitude climbing and familiar with the Everest region." Better luck finding a yeti, in other words. The room echoed with laughter.

"Well, I met her the other day," said the secretary who had chatted with Reynolds, as she entered the room to serve coffee. Heads swiveled, and soon the execs were picking their jaws up off the floor while the secretary recounted her meeting with Reynolds.

Not long after, the phone rang in Reynolds' hotel room. "G'day mate," an Aussie voice greeted her, "you wanna balloon over Everest?" Reynolds thought it was a climbing buddy pranking her and just said, yeah, sure. "Well, you're certainly game," the caller said. After he identified himself and described the project, she agreed to sign on.

No one cared to ask whether Reynolds had any ballooning experience. She checked all the boxes they needed.

In late September 1985, Reynolds was aboard the Zanussi, a high-altitude balloon, as it launched slightly behind schedule toward Everest from Kathmandu. The late start proved fateful: An up-valley wind chased the balloon, making it hard to control.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Jan Reynolds

- Jan Reynolds in an oxygen mask with a hanging camera, flying a hot-air balloon over Mount Everest

The balloon ascended to 28,000 feet, a new altitude record, but the wind made it impossible to sail over the mountain, so the goal shifted to finding a shoulder of Everest where the crew could safely set down. The pilots, Brian Smith and Phil Kavanagh, briefly argued about when to begin deflation, but an updraft almost sent them crashing into a cliff. That took the decision out of their hands. The wind-wracked rig dropped quickly — and snagged on some trees. Before the crew could react, there was a loud CRACK. The basket hit the ground and rolled, trapping everyone underneath.

Reynolds knew her companions had little experience in these conditions; in fact, neither man had even camped out in the snow before. Reynolds had, of course, and knew this was no time to be scared. "There is no room in your brain for that when things are going down," she said. "You have to stay focused and not hesitate."

Flames from one of the balloon's gas tanks shot up inside the overturned basket. The crackling of the fire was nearly deafening. Smith was tangled up in the rapid deflation cord, and Kavanagh was immobilized by a backpack. Reynolds could not move toward the flames without risking terrible facial burns. The pilots were screaming for her to put out the fire.

"I clawed and scratched my way from under the basket still encumbered with my chute and beat the flames out with my blistering hands," she wrote in her book. The pain was muted by a rush of adrenaline, and the fire slowly gave way to her furious thrashing. All the while, Reynolds felt an almost irresistible urge to run, run far away, knowing that the balloon's remaining gas tanks could blow up at any moment.

"If I had run there's a good chance my pilots wouldn't have survived the blow up," Reynolds wrote. "To this day, Brian and Phil still think I was thrown from the basket. They said there was no way I could have made it out from under that fast. When I showed them the melted hood of my parka explaining that the flames under the basket were right by my head and I couldn't turn my face they just shrugged. But I know that I too was trapped, and though it took effort, I managed to extract myself because I had that kind of burst of strength."

The crew's radio suddenly came alive with the voice of Chris Dewhirst, the expedition manager. Once assured that everyone was in reasonable shape, Dewhirst told the crew that, despite falling short of the ultimate goal, it had made "the highest bloody Alpine flight in history!"

For Reynolds, the doubt of her male crewmates was the price she paid for the opportunity to set records. A psychological tollbooth. She paid the fee and moved on.

A Change of Career

"I'm always the eternal beginner," Reynolds said, referring to the number of new things, or "firsts," she's attempted. "I'm always throwing myself into the unknown to see if I'll measure up to the task."

In the late '80s, Reynolds decided to cut back on altitude and concentrate on aptitude. A ruptured disc in her back aided that decision, as did her domestic circumstances. Her relationship with Gillette — who would be killed by bandits in Pakistan in 1998 — had ended. Subsequently, she married Javin Pierce, in a ceremony in the Himalayas under the looming shadow of Everest. Their relationship, which did not last, produced two sons: Briggs, now 28 and Story, 24.

At home in Stowe, Reynolds sharpened her skills as a photographer and began writing more frequently for outdoor interest publications and National Geographic, including one article about her solo crossing of the Himalayas from Nepal to Tibet and another about the ancient Silk Road trade route from eastern China to the Mediterranean Sea. This paved the way to a new career documenting the lives of Indigenous peoples around the world.

The people she encountered in her travels, Reynolds explained, "left such a deep impression on me, as I saw how well they treated each other because they needed each other to survive."

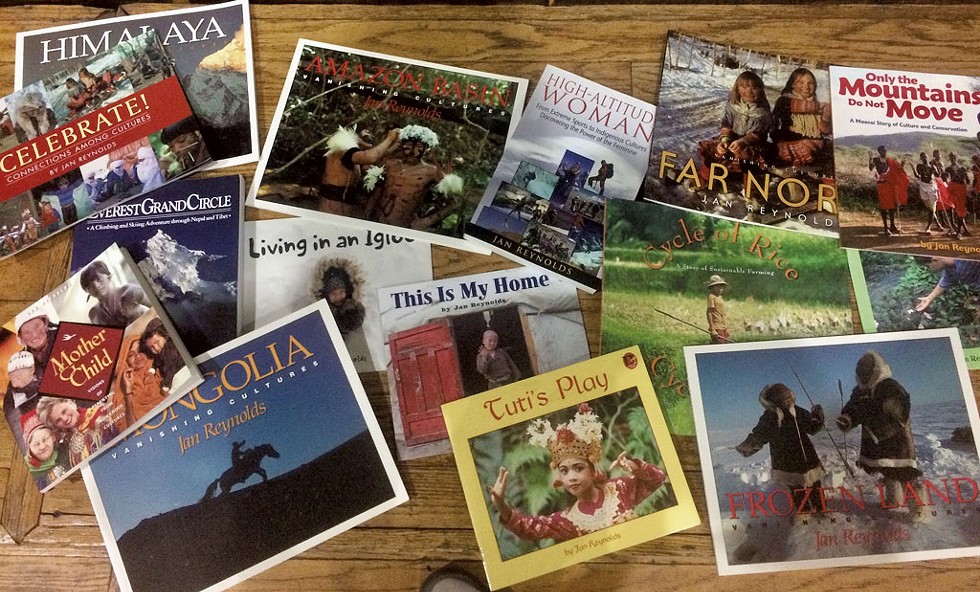

Her Vanishing Cultures children's book series was born in 1991 as a way to share these travel experiences with kids. Reynolds has lived with and written about the Tuareg in the Sahara, the Tibetans in the Himalayas, the Sami reindeer herders in northern Finland, Aboriginal communities in Australia, Mongolian tribes and the Yanomamo people in the Amazon rain forest.

"By sharing an empathetic and unsentimental glimpse" of these peoples, the New York Times wrote of Reynolds' Vanishing Cultures series in 1992, "she gives us all a great gift."

Her 1996 book, Mother and Child: Visions of Parenting From Indigenous Cultures, is a photo-rich compendium of lessons learned from these tribes, in particular their communal sense of caring for one another.

Although her Vanishing Cultures series is complete, Reynolds continues to work with Indigenous peoples for other projects. Published in 2020, The Lion Queens of India tells the story of endangered Asiatic lions and the Hindu and Muslim women rangers who protect them.

Reynolds' ability to stay in the background has been helpful in gaining the trust of the tribes. "I've always flown under the radar, but I feel like that, in some ways, is a superpower," she said. "It doesn't help me get books into adults' and children's hands, but to garner my material overseas, it is great. As a woman alone, I'm nonthreatening. The Indigenous women come to like me all right; I bring gold and silver jewelry and wool and silk scarves to trade. I hang out with their kids, and the men aren't threatened."

Two Vermont philanthropies, the James E. Robison Foundation in Stowe and the Lintilhac Foundation in Shelburne, have supported Reynolds' work with Indigenous groups.

Former Stowe neighbor and friend Stephen Plowman trekked with Reynolds in Mongolia. "It was the vision of introducing children to the beauties and depths of different cultures that guided her," he wrote from New Zealand by email. "The personal connections she formed with these remote people created a magic that was inspiring to behold."

Grounded in Vermont

Reynolds puts on her ski bibs one leg at a time — just like mortal folk. When she's not traveling, her days at home are routine by design. Her mother was a strong advocate of routine, arguing that it was the key to feeling secure and in control.

"As much as I like adventure and the unknown," Reynolds explained, "it's living in Vermont, and feeling very grounded, that allows me that freedom to go for it."

On a typical day, she's out of bed between 5 and 6 a.m. In the mornings, Reynolds works in a ground-floor office in her two-story house on Mountain Road. The house is earthy-looking, set back from the road, blending in with the surrounding woods. Natural light pierces large windows, illuminating artwork collected from her travels all over the world.

The project currently occupying Reynolds is a book about the Bajau people of Indonesia, a tribe also known as the "sea gypsies." She visited last fall. The research demanded underwater photography, so she got certified in scuba at age 66.

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Lewis Coty/jan Reynolds

- Jan Reynolds on light backcountry skis with friend Liz Soper on top of Sterling Ridge in Stowe

Reynolds runs on coffee, and her refueling stops serve as interludes between stocking the woodstove and other homely tasks. She does not feel fully awake until she is doing three or more things at once — loading the stove, boiling water for tea, doing yoga. She bounces up and down a lot, using short bursts of activity to maintain concentration and stay fresh.

"If I want to put in the classic eight hours [of work], I can be done by early afternoon," Reynolds said. "Then I take off for fun and phys ed, as I call it — getting fit, or at least staying that way ... skiing, kayaking, mountain biking."

If Reynolds sees fresh powder out her window as she awakens, well, to hell with the routine.

"Forget it. I'm out ripping it up," she said. "I don't make a lot of money doing what I do, so I need to take advantage of organizing my own time. I'd be a fool if I didn't."

She doesn't prefer one type of ride — she can go from skinny skis to snowboard depending on the snow and her mood. "I choose the tool based on the environment and the situation," she explained.

Reynolds is no ascetic; her secret vice is typical of someone raised on a dairy farm: ice cream. Her training runs when she was attending UVM took her past the old gas station in Burlington where Ben & Jerry's was starting up, and Reynolds got to know the team. She figured out how to time her run to show up just as the workers were pulling the paddles out of the ice cream makers.

"They would let me lick them clean before they washed them," she said, "so I got to try everything new."

Typically, Reynolds will plan overseas trips between November and April. Otherwise, she works and plays at home.

Some Vermonters know her name, but "most people don't know the things I've done or been through," Reynolds said. "Imagine at a cocktail party if I started with, 'Yeah, I took a hot-air balloon over Everest, and we crashed, but I put the fire out with my bare hands, but then I [went] hundreds of miles into the Amazon territory and a Yanomamo brave tried to make me his wife, but I escaped, and when I soloed over the Himalaya into Tibet, the Chinese army chased me down to shoot me, but I skied away...' [People] would think I'm a psychopathic liar."

At her Hall of Fame induction on March 24, Reynolds will have three minutes to thank everyone and perhaps dispel any thought that she spends time worrying about having received insufficient recognition during her era.

"You know, my climbing and skiing was the joy," she told Seven Days, "and maybe it inspired people by showing what humans could do — or maybe showing women that we can do anything guys do."

As she decided many years before, "I just loved being outside and going hard. Having fun."

The original print version of this article was headlined "Woman Wonder | The U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame recognizes Stowe adventurer Jan Reynolds"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Outdoors & Recreation, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Seven Days Aloud, Sports, skiing, snowboarding, Jan Reynolds, U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame, Seven Days Aloud, Video

About The Author

Steve Goldstein

Bio:

Steve Goldstein is a veteran newspaper reporter, mainly with the New York Daily News and the Philadelphia Inquirer. He served as Moscow and Washington D.C. bureau chief for the Inquirer. He has traveled to 73 countries and reported from most of them.

Steve Goldstein is a veteran newspaper reporter, mainly with the New York Daily News and the Philadelphia Inquirer. He served as Moscow and Washington D.C. bureau chief for the Inquirer. He has traveled to 73 countries and reported from most of them.

More By This Author

Latest in Category

Speaking of...

-

High School Snowboarder's Nonprofit Pitch Wins Her Free Tuition at UVM

May 1, 2024 -

UVM Swimming and Diving Overcomes Budget Cuts to Win Conference for the First Time in Its History

Mar 13, 2024 -

Two Vermont Teens Take On the Cross-Country Junior National Championships

Mar 6, 2024 -

Michael Krasnow Has Spent Decades Giving Kids Skis, Snowboards and a Taste of Independence

Jan 31, 2024 -

On-Slope Video Technology Captures All Your Downhill Runs Without Gaps, Gaffes or Frozen Fingers

Nov 8, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: