Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

The Mighty Bucks: Pro-Football Dreams Lead Vermonters to a Humble Arena

Published June 12, 2019 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 18, 2019 at 9:15 p.m.

The New England Premier Sportsplex, in Danvers, Mass., advertises itself as a place for batting practice and birthday parties. Its 200-foot-long indoor turf field typically hosts Little League baseball and youth soccer clinics. Next to a small concession stand in the main lobby, there's an arcade game that, for a couple of quarters, will measure how hard you punch. Its locker area doesn't include showers, but the facility has a row of bleachers for family and friends. The pitched roof is just high enough to accommodate a football pass.

The 14 members of the Vermont Bucks expected more from the venue in which they would play their first indoor football game as near-professional athletes. They had been preparing for this contest for months and dreaming about something like it for years.

Instead of a welcome, after a long drive in two rented vans, they found the owner of the opposing team hunched over the turf field, spraying red and black hash marks onto its 50-yard span. Paint fumes permeated the facility. The goalpost uprights still lay unassembled in each end zone.

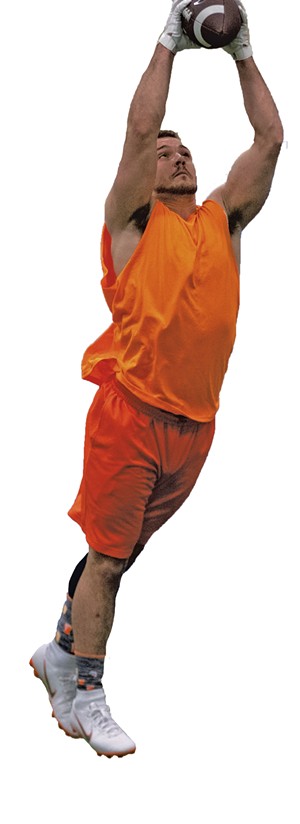

Hunter Nunes-Wales, 19, had put on a button-down shirt for the occasion. "I think we got overdressed," he said to a teammate as they waited outside, to avoid the smell.

Nunes-Wales — five foot nine, 190 pounds and bursting with raw athleticism — is trying to get to the National Football League. The last time a Vermonter managed that was in 2001, when Nunes-Wales was still a toddler.

He lives in Isle La Motte, on a farm owned by his adoptive parents. He took their surnames after the state removed him from the custody of his biological father. Last summer, the Burlington Free Press told Nunes-Wales' story and, with it, published a haunting photo of him sorting through rubble of the since-demolished apartment building where he endured physical abuse.

At the time, Nunes-Wales' performance as a running back and linebacker at Missisquoi Valley Union High School had just earned him a spot on the roster at Castleton University, a National Collegiate Athletic Association Division III program that does not offer athletic scholarships but represents the highest level of football competition in Vermont.

During the preseason Nunes-Wales tore a knee ligament, then started drinking and skipping classes. He dropped out and moved home. Now he works at a beer distributor for $15 an hour.

In search of a way back to the gridiron, Nunes-Wales landed this spring on football's island of misfit toys: arena league, an indoor riff on the sport where cast-asides from the NFL's college pipeline toil for a second chance.

Arena football compresses the game down to the size of a hockey rink — it's 50 yards, instead of 100 — and reduces the number of on-field players per team from 11 to eight. Instead of running out of bounds, receivers tumble over padded boards. The enclosed environment encourages a frenetic pace and high scores, like a pigskin pinball machine. Professional arena leagues have imitated NFL glitz for decades but struggled to replicate its glory. A tantalizingly few players, however, have managed to cross over, including Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Kurt Warner and former New England Patriots wide receiver David Patten.

Nunes-Wales joined the Vermont Bucks, a once-professional arena team that played one season in Burlington, in 2017, using players recruited from across the country. New owner Joanna Morse has ambitions of restoring the franchise to a level that attracts the region's finest athletes. This year, Vermont athletes were all she could afford. Morse reincarnated the Bucks as a semipro "professional development" species, where the players plunked down a fee to compete. Their games were all at the Danvers Sportsplex, outside Boston.

Football players are a rare breed in Vermont, and those who will pay to play are even fewer. Shorthanded for their comeback game, the Bucks would need Nunes-Wales to line up on offense, defense and special teams.

The Bucks' opponents, a New England Patriots knockoff called the New England Cavalry, arrived with branded bags and hoodies. Their players were more than formidable. A six-foot-three, 380-pound lineman would defend their quarterback, dubbed "the Human Joystick" for his crafty quickness.

"They're huge, plain and simple," Nunes-Wales said.

But on a football field, Nunes-Wales felt no fear. It was the place where his troubles and failings fell away, where he always found an opening to run. "My sanctuary," he called it. He couldn't not play.

Nunes-Wales and his teammates changed into their new safety-orange uniforms, strapped on reconditioned helmets and lined up for kickoff.

Orange You Psyched?

There was a brief time in Vermont when the pursuit of professional football didn't require such a humbling detour. The previous version of the Bucks introduced the indoor game to Burlington in the spring of 2017. Part-time NASCAR driver and South Hero native Tim Viens bankrolled the team with an investment of nearly a half million dollars. His team competed on one of the state's most prominent competitive stages, the University of Vermont's Gutterson Fieldhouse. In its inaugural year, the team secured a major sponsor in Heritage Ford and won a Can-Am Indoor Football League championship. The Northeast Sports Network broadcast its games.

Viens seemed to have found a paradoxical niche. Football in Vermont was in bad shape, so roughed up that in September 2017 the Wall Street Journal suggested that it might become "extinct." The following year, Burlington and South Burlington high schools would combine programs so they would have enough kids to field a team.

No reliable tally of Vermont high school football players exists, though even the Vermont Interscholastic Football League's executive secretary, Bob Hingston, acknowledged that participation has "gone downhill."

High school football teams require dozens of players, so they're often the first athletic programs to crack as Vermont school enrollments shrink, Hingston said. The sport is further plagued here, as elsewhere, by concerns around the potential lifelong side effects of concussions. HBO's documentary show "Real Sports" recently reported that the concussion crisis may be leading to white flight from youth football as affluent families spurn its inherent health risks. And Vermonters who do play must leave the state to elevate their game. There are no local scholarships to chase, and only a few Division III colleges and adult amateur teams to cheer.

Viens' Bucks brought flair to a sport in need of a spit shine in rural New England. Players stormed onto bright orange turf at the Gut each week through a giant inflatable helmet and a cloud of smoke. Dancers wooed crowds of up to 2,000-plus, flanked on the field by Heritage Ford trucks and SUVs. An antlered Bucks mascot high-fived young fans, and a DJ spun tunes. The kickoff for the inaugural home game, in March 2017, was delayed 30 minutes because the pregame show blew an electrical fuse. During the game itself, beer-toting spectators and their children leaned against the sideline boards, right next to the action.

"It was wild," recalled Ed Hockenbury, one of UVM's associate athletic directors.

"It was much different than what you'd see with our games," said Gregg Bates, a UVM associate athletic director, referring to Catamounts hockey. "It brought in a different crowd."

The game's NFL-like atmosphere blew away Brendon Hutchins, a former high school player in St. Albans who had gotten tickets for his 19th birthday.

Hutchins had already run up against the limits of playing competitive football in Vermont. He discovered the sport as a heavyset high school first-year and managed to transform into a chiseled team captain by his senior year at Missisquoi Valley Union. He played at Castleton for a year but dropped out, he said, due to the cost of tuition.

"It was shattering," he recalled. "Having to hang up the cleats and not know if I was going to play again was really, really hard on me ... It felt like I was always going to have to wonder, What if? And living with what-ifs is not fun."

Hutchins' birthday game at the Gut planted another one.

"Sitting there, watching that game, I definitely had that thought in my head: This would be so cool to be in this uniform, with so many people around, playing," he said. "It would be a dream come true."

Two years later, he'd get his chance to understand how it felt. The team no longer had smoke machines or dancers, just a bright orange jersey with Hutchins' name on the back.

He put it on in Danvers as he suited up to pursue the Human Joystick.

Homegrown Players

As the Bucks' 2018 season neared, Viens sold the team to a group of New Hampshire and Massachusetts men. Within a month, the new owners abandoned the project. The reason was never made clear. Viens said the buyers didn't actually have the money to cover the deal. They told Vermont media at the time that certain terms of the sale hadn't been met.

The Bucks' collapse was not shocking in an arena industry known for grand visions that fail to deliver. Morse, an accountant, said she had been the Bucks' vice president of operations, in charge of contracts, player housing, sponsorships and marketing. "You name it, I did it," she said. Morse had helped the team build a foundation for success, only to see it disappear as "a lot of shady, under-the-table stuff went on" with the sale.

She sued Viens last year, claiming he walked away from the team without honoring the remainder of her employment contract for the second season, worth about $33,000. According to her civil complaint, Morse and Viens had agreed that she would move up to become president of the club in its second year. In a recent interview, Viens was dismissive of Morse's contributions, referring to her as his "part-time secretary."

Morse worked at Burlington College until the school shut down. She's professional, gets to the point and usually has an iced coffee in her hand. She's also thrifty and unpretentious. When a player arrived at a game without his black socks, she offered to loan him her black nylon tights.

Morse, 38, is also a mother in a football household in Colchester. Her son started playing in the first grade. Between helping organize youth leagues and watching him compete throughout high school, Morse saw the challenges that players face in Vermont. She heard coaches disabuse her son of expectations that he could take it to the next level. He's heading off to college next fall to play football for the University of New England.

If Morse was a part-time secretary, she was a secretary with a bold new vision for the team her former boss had let slip away. Instead of importing talent from around the country, she would try to cultivate Vermont players, like Hutchins, who had skills but nowhere to showcase them. In turn, Vermonters would rally behind the team and, over time, the Bucks would become the pride of Vermont.

"I put so much effort into this team, I'm not going to just walk away and let it go," she said in March. "I know I have the skills and the ability to do this."

There was one glaring problem with Morse's plan: She didn't have money. Without financial backing, bringing back a professional-level team with a home-turf arena and paid players was out of the question.

"There can be a lot of publicity and a lot of hype, but if you don't have serious people behind it, providing solid funding or base, it's not going to go anywhere," said Bob Johnson of the Vermont Principals' Association, which oversees high school sports.

But by starting out as a travel-only team with unpaid players, Morse managed to cut out more than 90 percent of the expenses. She convinced a family friend to cover the rest. She needed time, too, to earn back the trust of fans and sponsors. A spring 2019 season would be the demonstration project. Her prodigal Bucks could then return to the Gut in 2020 having earned their stripes, ready to go pro.

'Officially a Buck!'

Practice began in a cramped conference room, where Morse first went over the fine print. The mandatory cost to play was a league fee of $50. Jerseys — if players wanted their name on them — were another $55. Optional accident insurance, to defray the costs of any injuries, was $31 a month, an Aflac salesperson explained. Players were also responsible for their equipment, though Morse had managed to acquire a stash of used helmets. Their 10-year service life had recently expired, but with some TLC and a fresh coat of paint, they'd suffice for a short arena season.

More fine print: Playing in an arena league can jeopardize athletes' amateur status, which means they can't return to college to play. Nunes-Wales didn't realize that until the following weekend's practice. He was talking about his prospects of playing at a junior college when a teammate chimed in about the potential eligibility issue.

"I'm probably not going to a juco school, then," Nunes-Wales said, shrugging it off. His new Bucks team was already beginning to jell. By mid-March, tryouts had yielded 19 players for a roster with 21 spots. Players had signed contracts at a plastic table in front of a Bucks logo so Morse could snap a photo to promote them online.

Some recruits were college graduates with professional careers, including wide receiver Jordan Goodrich, a special educator who played at Castleton, and former UVM club team quarterback Jack Leclerc, a software developer.

Andrew Knapp, a veteran, father and recruiter for the Vermont Army National Guard, said he tried out as a way to challenge himself. He hadn't competed since he was a kid. Blaine Tardy, a five-foot-10 lineman, wrote in a signing note posted to the Bucks website that his goal was to block well for his younger brother, Nunes-Wales.

Making the team was a "huge landmark" for Hutchins, who had been staring down a potentially football-less future after withdrawing from Castleton. He posted to Instagram an image of a text message in which coach Jeff Porter invited him to officially sign with the team. "To all of those who doubted me and still continue to doubt me, I feed off your negative energy," he wrote. "Officially a Buck!!!!"

Porter set the tone. The club coach at UVM, Porter looks like an old-school gym teacher with his balding head and red face. He has a drill sergeant's voice, but he utters only encouraging words. "He doesn't ever yell at us," Hutchins said. "He'll guide us and put us in the best position to be successful." Hutchins had aimed to play on Porter's team in college, but he wasn't accepted into UVM's athletic training program. Before his rejection, Hutchins recalled that Porter drove to his family's gym in Swanton to drop off a team jersey for Hutchins.

Porter's encouragement was infectious. The Bucks began to see their collective talent. Kicker Josh Taylor, a graduating UVM senior who played on the school's club team, noted his new teammates' strength and speed. He said he had never seen a squad this good.

'Committed'

Away from the practice field, the season was off to a rougher start. Sponsors weren't interested in advertising with a team that had no home turf. UVM made clear it couldn't host an arena team in 2020 while the Gut underwent renovations. In April, Morse's sole investor-friend pulled out.

Morse also faced competition for whatever arena niche in Vermont might still exist. A former Bucks assistant coach, Claude Flynn of Atlanta, and equipment manager Michael Mazzella, a science teacher at Rice Memorial High School, announced they were partnering to create an arena team in Middlebury called the Vermont Brew. They were preparing to play in 2020 and had already secured a home field in the Howard E. Brush Arena at the Memorial Sports Center, Mazzella said. Like Viens' Bucks, they intended to pay their players, whom they would pull from across the country and house in Addison County for four months each year.

Morse was still hanging on to one advantage: Her team had a league. Morse signed the Bucks to play in the upstart New England Arena League. Its Darwinian adaptation in the capricious business of arena football was that all teams would compete at one central field. The NEAL's approach lowered the barrier for entry and enabled other shared benefits. The league would broadcast each game live online so fans could watch and players could collect film. The players' league fee was supposed to guarantee them online statistics and bio pages that would help them get noticed by scouts.

The league's creator, Kevin Corbin of New Hampshire, also owned its keystone team, a former pro club called the New England Cavalry. Such arrangements are common in arena football; they also pose an obvious conflict of interest. Morse said she had been assured a neutral commissioner and board members from each club would control the NEAL to ensure fairness.

But warning signs emerged. Two teams dropped out, leaving the league with four, including the Bucks and the Cavalry. When the league's arrangement with a host field in Rhode Island fell apart, the season had to be pushed back to mid-May and relocated to Danvers. Corbin began describing the 2019 campaign as a "beta model."

Players, meanwhile, gossiped about Corbin's colorful rap sheet, which included a bizarre 2017 encounter with Salisbury, Mass., police that began outside a strip club. He was arrested. Later, in a cell, an irate, naked Corbin allegedly used his own urine and feces to block a jailhouse security camera. (He pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct but denies the allegation regarding the camera.)

"There are some days where I wake up and I'm like, Why am I doing this? What am I doing?" Morse said. "But I've committed, and I have a group of people who have committed, and I'm going to stick to my commitment."

So Morse rented a pair of vans for game day and told the team to meet at the Colchester Park and Ride at 8:30 a.m. for the trip to Danvers. Like some of her players, Morse dressed with swagger for the team's debut, in a black pantsuit, hoop earrings and sunglasses. Like her players, Morse said she wasn't sure what to expect.

"I have no idea," she said. "I try to think positively."

Game On

Fewer than 100 spectators occupied the Sportsplex, counting the players and the dads, moms, girlfriends and siblings who'd made the four-hour drive from Colchester to watch.

But as soon as Corbin's Cavalry kicked off, it sounded like 1,000. The claustrophobic venue amplified every bit of the intensity that had been building for the past three months. Noise from every cheer, whistle, play-by-play call, yell, thud and crunch had nowhere to go but to bounce off the concrete walls and ceiling and collide back over the field.

From the sideline, each play became dizzying and terrifying, a tangle of 16 human springs uncoiling at once, a microburst within a thunderstorm of human energy.

The Bucks opened with a play none of them had ever tried in a game because, outside arena football, it'd be illegal. One of arena football's quirks is a rule that lets one wide receiver run forward before the snap. Nunes-Wales lined up several yards behind the line of scrimmage, then sprinted toward it a second before Leclerc called "hike." He juked outside and caught a pass wide-open in the end zone. The Bucks lined up for a two-point conversion — Taylor, their kicker, was missing the game to attend his college commencement — and scored on an end around. The score was 8-0.

The Cavalry returned Nunes-Wales' kickoff deep into Bucks territory. On defense, Hutchins blitzed on the first play through a gap in the offensive line. A five-foot-seven, 255-pound bowling ball of a fullback stepped in his way. Hutchins bounced off him and scrambled toward quarterback Marquis Eberhart, who was already living up to his Human Joystick nickname. Eberhart pivoted to evade Hutchins' outstretched arm, rolled right and threw a dart pass on the run.

The Bucks' defense broke up that pass but couldn't contain him for long. The Cavalry scored three consecutive touchdowns.

Slender, pale and tattooed, Corbin was out on the turf, screaming at his players before each snap. Whenever confusion over the rules or a call arose — which, with only two referees, happened frequently — Corbin jumped into the fray. When the Bucks, down 8-22 in the second quarter, threatened to score again, Corbin convinced the referees to call a "five-minute warning" time-out.

"He's making his own rules, right?" one of Cavalry coaches said to the Bucks sideline.

The Bucks scored after the time-out. They needed only one more touchdown to tie the game.

On the next drive, Leclerc rolled right and threw a 15-yard pass to wide receiver Goodrich, who made a diving catch behind the defensive back for another touchdown. Goodrich shimmied as he sat up on the turf. His teammates swarmed.

Somehow, it was still the second quarter, though no one knew how much time was left. The Cavalry had scored once more, and the Bucks were near midfield, down 20-28. Leclerc pitched the ball, and Nunes-Wales dodged four tacklers but couldn't gain a yard. On second down, Leclerc threw the ball away to avoid a sack.

But something was wrong with Nunes-Wales. He walked off the field, wincing. A defender had hit him headfirst in the torso. "I broke a rib," Nunes-Wales said, choking back tears. He pounded both fists on the bench.

Knapp asked Morse to find the medical staff, which had been promised in league flyers, along with "player safety & concussion protocol." Corbin pointed to his sideline and yelled "Trainer!"

The trainer hobbled over on crutches.

As the man began applying white athletic tape to Nunes-Wales' rib cage, the Bucks turned the ball over on downs. Eberhart joysticked his way to a touchdown on a long scramble. He completed a two-point conversion with a pass to his 380-pound lineman. A few players started shoving. The Cavalry recovered their own kickoff, then scored again as the half finally expired. The score was 20-44. There were still 30 minutes to play, and time was not on the trailing Bucks' side.

"It'd be different if I wasn't getting beat on every play," Nunes-Wales said. "Playing offense, defense and special teams, it takes a toll on you ... But we don't have enough players."

He had pulled up his jersey and removed his pads to relieve the pressure on his ribs. He wanted to keep playing, he said, "but they won't let me."

Homeward Bound

When the game ended, the teams shook hands and posed for pictures together on the field. The scoreboard read Cavalry 74, Bucks 46, but the scorekeeper had lost track during the first half.

The Bucks stuffed their sweat-soaked jerseys in their bags, loaded their pads into the vans and settled in for a pungent trip home. They were tired but not defeated. The day had raised questions about the league, but it answered any the Bucks had about themselves. "We still held our own against them," Hutchins said later. "We're the new team on the block."

The players in Porter's van decided to watch film from the game. The recording, taken by a Massachusetts company that specializes in youth sports, wasn't as professional as they'd imagined. Much of the footage was shot from behind a net, was blurry or cropped out part of a play. It wasn't going to attract many fans or pro scouts.

They skipped forward to the second-quarter touchdown pass from Leclerc to Goodrich that had nearly tied the game. Leclerc tapped Goodrich's cellphone screen to zoom in on the receiver's celebratory dance. They passed the phone around so everyone could watch it.

If they'd turned up the volume, they would have heard what the surprised announcer had proclaimed over the crowd's din in his nasal Boston tone: "The Vermont Bucks just won't give up!"

Postgame

X-rays showed that Nunes-Wales' rib was bruised, not broken, and he scored four touchdowns in the Bucks' next game. They won it, and the one after, against disorganized teams that turned out to be little more than practice squads with some Cavalry players sprinkled in.

The Cavalry did not play their other scheduled league games and instead traveled to West Virginia to face a professional team. Referees in that game ejected Corbin for arguing a call. Short on players and frustrated with the league, the Bucks decided to skip a "championship" game against the Cavalry last Saturday, ending their season.

Morse and her players are still chasing their dreams. Hutchins and Nunes-Wales said they plan to play in outdoor adult amateur leagues this summer. Morse is looking for a home field for Bucks games next spring.

Correction June 13, 2019: A previous version of this story misidentified the Howard E. Brush Arena in Middlebury.

The original print version of this article was headlined "The Mighty Bucks | Pro-football dreams lead Vermonters to a humble arena"

Related Stories

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: Culture, football, arena football, Vermont Bucks, Joanna Morse, Brendon Hutchins, Josh Taylor, Jeff Porter, Hunter Nunes-Wales

More By This Author

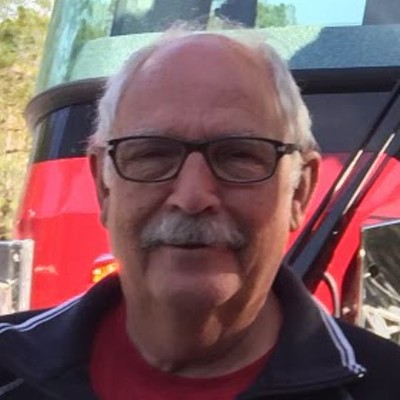

About The Author

Derek Brouwer

Bio:

Derek Brouwer is a news reporter at Seven Days, focusing on law enforcement and courts. He previously worked at the Missoula Independent, a Montana alt-weekly.

Derek Brouwer is a news reporter at Seven Days, focusing on law enforcement and courts. He previously worked at the Missoula Independent, a Montana alt-weekly.

About the Artist

James Buck

Bio:

James Buck is a multimedia journalist for Seven Days.

James Buck is a multimedia journalist for Seven Days.

Speaking of...

-

Performers in Drag Shine at Burlington High School Halftime Ball

Oct 16, 2021 -

Backstory: Most Vicarious Reporting

Dec 25, 2019 -

Second Down: Buffalo Bills Hire Former Dartmouth Football Coach Callie Brownson

Sep 3, 2019 -

Talking Patriots With Vermont Author Glenn Stout

Nov 28, 2018 -

Dartmouth Coach Callie Brownson Is a Pioneer for Women in Football

Oct 24, 2018 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.

- 1. Pride Center of Vermont Is Roiled by Allegations of Antisemitism LGBTQ

- 2. Video: Retired Couple Live Sustainably Off the Land at Birch Hill Sugarworks in Jericho Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Olympian Ilona Maher to Compete on 'Dancing With the Stars' Arts News

- 4. Secondhand Shopping In and Around Montréal's Mile End Québec Guide

- 5. The Seven Days Guide to South End Art Hop 2024 Art Hop Guide

- 6. Sandglass Theater Brings International Puppetry to Vermont Performing Arts

- 7. Five Open Studios to Visit at the South End Art Hop Art Hop Guide

- 1. Three to Six Hours in Rutland, the Marble City Culture

- 2. Video: Teatime at Summersweet Garden Nursery in East Hardwick With Rachel Kane Stuck in Vermont

- 3. Video: Burlington Burn Club Builds a Fire Community Stuck in Vermont

- 4. Maher Madness: Olympic Bronze Medalist Comes Home to Burlington Culture

- 5. The Seven Days Guide to South End Art Hop 2024 Art Hop Guide

- 6. Pride Center of Vermont Is Roiled by Allegations of Antisemitism LGBTQ

- 7. Secondhand Shopping In and Around Montréal's Mile End Québec Guide