Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Business

Cannabis Company Could Lose License for Using…

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

What Vermont’s Classic American Diners Tell Us About the Current State of Restaurants

Published July 3, 2024 at 10:00 a.m.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

The diner of my childhood was Arlington's now-shuttered State Line, a white-sided single-wide, surrounded by a cornfield, that straddled the Vermont-New York border. The more I recall about the place, the more I think I made it up: pancakes as big as my head, a crackly radio soundtrack (usually country) and a cat that walked across the tables as it pleased. The only traces of the State Line's existence online are a glowing, incredibly detailed Yelp review from 2010 — five stars! — and a photo essay depicting its now-abandoned state.

I moved on to hungover college breakfasts of sausage gravy over biscuits at Henry's Diner in Burlington. Then it was late-night tuna melts and turkey clubs at Brooklyn's 24-hour Neptune Diner II. Each diner met me where I was in my life without altering a darn thing about itself.

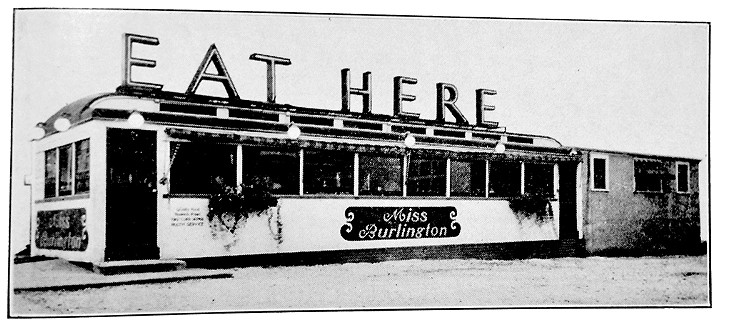

The iconic, metal-clad façade of a classic diner gleams in the sunshine, a beacon of consistency for weary travelers seeking bottomless cups of coffee and quick, cheap eats. Henry's has been in the same Bank Street spot for nearly 100 years, long outliving opposition from churches and society people when Henry Couture opened it in the 1920s. The "greasy spoons," as they were often known, had a bad reputation at the time, according to local historian Bob Blanchard. Their initial clientele were male laborers — who gathered for heavy meals after late-night factory shifts — and shifty characters, as depicted in radio programs and magazines of the time.

But diners have been staples of American cuisine from their origin as horse-drawn lunch carts at the turn of the 19th century through their latter-day evolution to converted rail cars or prefabricated replicas.

They thrived during Prohibition, when saloons were closed, and during the Great Depression, thanks to their low prices. They became roadside stops for long-haul truckers and, after World War II, destinations for working-class families. Many were run by recent immigrants, who infused the menu with dishes from home.

Diners change with the times without changing much at all. Some now have added kitchens or attached dining rooms to host a crowd, but their counters and patched vinyl booths remain, showing the patina of time. Meals are often delivered by women who generally still embrace the title "waitress" rather than the modern, nongendered "server." But you can now pay with a credit card most places, and, at least in Vermont, the maple syrup is almost always local.

But sometimes they do need to adapt, whether by raising the price of that bottomless cup of coffee or cutting hours. Restaurants have been dealt blow after blow since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, from increased food costs to short staffing to rising rents. Diners aren't insulated from those struggles. Some of the state's iconic cars are currently in the midst of redevelopment projects, for sale or closed altogether.

A few classic dining cars have endured but been repurposed as restaurants with distinctly non-diner cuisine, such as high-end T.J. Buckley's in Brattleboro, which opened in 1983, and El Cortijo Taqueria in Burlington in 2011.

"It's going to be interesting as the older generations who really grew up in diners pass on," said Erin McCormick Torres of the blog Travel Like a Local: Vermont. "Will we keep that kind of nostalgia for diners in society?"

In researching her 2018 book, Classic Diners of Vermont, published under Erin K. McCormick, McCormick Torres found that locals and tourists alike are "extremely passionate" about their favorites. While many restaurants offer a diner-like experience, such as the Wayside Restaurant, Bakery & Creamery in Berlin, something unique happens within the physical constraints of a 15-foot-wide dining car. In these tight quarters, you're sure to get to know the person perched on the next stool — or at least overhear their conversation.

Diners, McCormick Torres said, have the ability to bring together different generations and people of all walks of life. Families fill booths, and regulars leave elbow prints on the same spot of a well-worn Formica countertop day after day. They're famously popular with politicians, who routinely make campaign stops at diners to signal that they can hang with the masses. Burlington's longtime Oasis Diner hosted both vice president Walter Mondale and president Bill Clinton before it closed in 2007.

"A diner in Vermont is more than its history and the structure in which it's built," McCormick Torres wrote. "What makes a diner a diner is the way it makes you feel and the role it plays as the heart of the community it serves."

Seven Days food writers headed out around Vermont to get a taste — of the over-easy eggs, pancakes, corned-beef hash, tuna melts, liver and onions, and pie of all kinds, but also of how these beloved establishments are adapting and continuing to serve those communities, from Bennington to the Northeast Kingdom. We stuck to businesses operating in classic train cars, whether a Worcester Lunch Car, Mahony, Silk City, Fodero or rebuilt Sterling enclosed in a wood frame; they've all got long counters with bolted-down stools and serve classic, all-American diner fare.

While our list is by no means comprehensive, these seven examples illustrate the challenges restaurants face right now — and show why the conversations that happen across those counters are often more important than the eggs and English muffins. "Some of these small towns have lost their key focal points," John Rehlen, co-owner of Castleton's Birdseye Diner, said. "I wanted to keep our village vital and alive."

In our travels, we learned how owners are adjusting their pricing, hours and offerings to survive — and exactly how full one can feel after eating a breakfast burrito-patty melt bang-bang at two diners that are only 40 minutes apart.

— Jordan Barry

The Usual

Birdseye Diner, 590 Main St., Castleton, 468-5817, birdseyediner.com

Jean Hayes estimates she's cracked at least a million eggs in her 32 years cooking at Castleton's Birdseye Diner. After the breakfast rush one recent Tuesday morning, Hayes added four to that running total. Each hit the flattop with a sizzle, joining sausage patties, fluffy buttermilk pancakes and corned beef hash crisping under grill weights.

Hayes pivoted to lower a basket of home fries into bubbling oil and checked a pair of poached eggs simmering on the stove before turning back to smoothly flip the eggs over easy. Each move flowed unhurriedly into the next.

Hayes, who turns 61 this month, wears her gray-streaked brown hair in a ponytail. She has a gravelly voice and laughs easily. Five days a week, she commutes from Fair Haven to start the morning shift at 6:45 a.m.

She likes the people she works with, and her regulars. "If I glance out and see someone come in, I already know what they want before the waitress puts it in," Hayes said.

But Hayes is eyeing retirement, counting down the five years and four months until she's eligible for full social security benefits.

"I'm just getting too old," Hayes said. "I got really bad feet now from being on my feet all day."

John Rehlen and his wife, Pam, bought the diner from Hayes's late husband, Tim, in 1996. "John talked me into staying," Hayes said. "I liked it, and I needed a steady job."

The Main Street spot has been a restaurant for about 80 years, according to Rehlen. The 1940's-era diner car built by Silk City Diners of Patterson, N.J., arrived in Castleton in 1968. A previous owner had covered it with barn board and a pitched roof, so the Rehlens hired a diner restoration expert to refurbish its original chrome-and-enamel splendor. But even the most meticulously renovated diner is an empty shell without a solid staff — and the enduring connections they build over years of serving the same customers.

Losing Hayes or her kitchen colleague of 24 years, 57-year-old Jeannie Patch, is not a scenario Rehlen wants to imagine — though he knows it's coming. Little Jean and Big Jean, as they're known, are as much of a Birdseye institution as the slabs of homemade meatloaf, scratch-made soups and signature slender onion rings.

"John will probably talk me into staying here if he's still alive," Hayes said of her 80-year-old boss, with a laugh.

"We can't find help," Hayes added, slathering butter on toast. Then she said jokingly to me, "You can do dishes if you want."

The dishes will get done, but the Rehlens have had to streamline to adapt to tight staffing. They no longer serve house-baked cakes, pies and muffins, and they've subbed boneless, skinless breasts for the whole roasted turkeys they used to pull apart for hot and cold sandwiches.

The diner is one of the Rehlen family's four downtown food and retail businesses. Birdseye accounts for 20 of the group's 60 full- and part-time employees, who range from international college students on short-term work visas to old-timers.

Dulcie Gibbs, 56, has waited tables at the diner for 26 years. She loves her regulars, she said, especially those she fondly called "my oldies."

Birdseye feeds a wide range of folks, and servers must be at ease with all. "You've got every walk of life in here all at once: tourists with the expensive house on Lake Bomoseen, the guy that's pouring concrete or the carpenter, the professor or the student," Rehlen said.

During my visit, weekly regular and retired state legislator Bill Carris of Wells said, "We walk in and they know what we want." In his case, it's an English muffin with bacon and a short stack with extra butter.

Patch popped out of the kitchen to deliver a blueberry pancake and a hug to Molly Faucher. Molly and her husband, Roland, drive from Mendon to Birdseye every Tuesday and Saturday "as a rule," she said.

Roland carefully set his Americal Division veteran baseball cap on the table next to his usual beverage — "iced tea, lemon, lots of ice." He'd had to explain his order to a new waitress.

— Melissa Pasanen

Bottom(less) Lines

Martha's Diner, 585 Route 5, Coventry, 754-6800, facebook.com/marthasdiner85

A cup of coffee costs $2.25 at Martha's Diner. That's 50 cents more than it was until December, owner Kathy Holbrook said, but it's still bottomless.

"It's sort of frustratin'," Holbrook said, dropping the "g." "The customers, some of them understand. But some of them think you're just trying to get rich off 'em."

Since the start of the pandemic, food prices have soared: The U.S. Department of Agriculture reports a 25 percent increase from 2019 to 2023, second only to transportation prices. Diners are known for cheap eats, but they're feeling the same squeeze. Eggs, fryer oil, hamburger and sausage — "the stuff you need every week," Holbrook said — have all gotten more expensive.

Coffee has jumped from $123 to $176 a box, which still makes roughly 1,600 cups of coffee. Holbrook orders two or three boxes every two weeks, she said. At an additional $53 a pop, that raises her biweekly bill by $100 to $150. As Holbrook's costs have gone up, she's had to make some tough choices about how to pass them on to her customers.

At first, she joked about rationing regulars who paid their $1.75 and drank five cups. But after more than two years of rising ingredient costs, Holbrook finally decided to up her prices at the Coventry diner, which she bought from her parents in 2002.

"I love my customers, but I need to stay in business," she said.

To get the best deal, Holbrook sources from a couple different suppliers. For every item she gets, she said, she shops around to find the best price. Switching from one supplier to another might save her $8 per case on eggs — and she orders eight or 10 cases per week.

"My ordering is time-consuming, because I try to save as much as I can," Holbrook said.

Now 54, Holbrook has been working at the diner since she was 15, when she started as a dishwasher. The chrome-plated 1953 Fodero Dining Car — manufactured in Newark, N.J., and brought to Coventry from its original home in Saugus, Mass., in the 1970s — has been in the family for nearly 40 years. Holbrook's parents bought it in 1985 and christened it "Martha's," after her mom.

Back then, the green-and-pink-accented diner opened at 4 a.m.; on weekends, Holbrook would join her mom there in the wee hours.

"I was not liking it very well at first, but I grew into it," Holbrook said. She became a waitress, then eventually moved to the grill — which remains right behind the counter, as many diner cars were originally designed.

Since her mom died in 2006, keeping things running "has always been on my mind," Holbrook said. "I want to make her proud." For the past 10 years, her daughter, Katie Breault, has worked alongside her. The rest of the staff of seven is mostly family.

On a Monday in early June, the late-morning crowd was also mostly local families, filling several of the diner's bigger booths. At the counter, the topic of the day was the past weekend's fishing derby — not who caught the biggest fish, but a young participant's reluctance to unhook the one they caught.

"It was too slippery!" the waitress yelled down the counter, laughing as she carried a plate of waffles out to one of the booths.

Most customers were eating breakfast, which Martha's serves all day. Dishes such as omelettes, plate-size pancakes served with syrup made 10 miles away in Barton and fluffy biscuits slathered in a rich, peppery sausage gravy account for 70 percent of business.

Along with coffee, some of the other menu staples have increased in price: One egg and toast is up a buck, from $2.95 to $3.95, and a single pancake went from $4.95 to $5.95. But not everything has gone up: At $9.95, two eggs with a hamburg patty and toast remains the most expensive breakfast item, along with several of the three-egg omelettes.

In October, before she'd raised any prices, Holbrook decided to close on Wednesdays. She was short on help and had worked 100 hours per week for four months, doing everything from frying eggs to managing the tricky ordering. But it was still a tough call. She chose Wednesdays — a day when other local restaurants are open — to make sure customers would have somewhere else to go.

"It's one day without worry," Holbrook said. "My mind is just free."

Like paying $2.25 for a cup of coffee — or five, depending on their definition of "bottomless" — her customers will get used to it.

— J.B.

Global Mix

Athens Diner, 46 Highpoint Center, Colchester, 655-3455, athensdinervt.com

The Athens Diner was closed last week from Sunday through Thursday — for a happy occasion. A sign on the door announced that the restaurant was taking a break "to celebrate the wedding of our No. 1 cook."

The No. 1 cook, Jessica Goulette, was marrying another diner cook, Warvin Gordon, after a meet-cute in the restaurant kitchen. A sweet love story, for sure, but also an unexpected outcome of owner Shawn Malone's desperate effort to staff his diner.

Gordon came to the Athens more than a year ago through an employment agency, to which Malone turned when all of his other efforts to recruit cooks had proved fruitless. The Vermont-based business — which Malone declined to name on the record to protect his secret weapon — has helped him cover several vacancies since 2022.

Most of the agency's workers have hailed originally from Jamaica, as Gordon does. They make up four of the team of 12 who keep things humming at the diner, cooking and serving cast-iron breakfast skillets, club sandwiches and Greek specialties, including chicken and lamb gyros.

Gordon's new wife, on the other hand, practically grew up in the diner. When Malone, 61, bought the Athens Diner in April 2021, Goulette's mother, Vicki, had been cooking at the Colchester diner for more than 20 years under two previous owners.

Mother and daughter worked together in the kitchen. When Vicki retired in 2023, Jessica took over as lead cook.

Another result of the wedding-prompted closure was that Malone gave himself a Sunday off. Since he became a first-time restaurant operator in his late fifties, cashing in his 401k to invest in the business, "I work seven days a week," he said. "I do everything. You name it."

Still, he saw it as "a chance to do something that I've always wanted to do," Malone said, sitting in one of his diner booths during a rare break. His 22-year-old daughter, Chloe, the restaurant's host/manager, had fetched him from the kitchen.

Malone, a New Hampshire native, has loved cooking since he was assigned mess hall duty as a young man in the U.S. Air Force. He went on to a career running information technology systems, but when he spied a for-sale listing for the Athens Diner, it felt like time to follow his dream.

"Diners are just a mainstay," Malone said, glancing with appreciation around the black-and-white tiled, red-accented 1953 Worcester Lunch Car.

As if on cue, a customer gushed her thanks to Malone as she walked past: "I've been coming here since it was Libby's. It's always the best breakfast."

Many of the diner's fans still call the diner Libby's or Libby's Blue Line, its name from 1989 through 2011, after the dining car moved from Massachusetts to Colchester.

Malone bought the Athens Diner from Bill and Naomi Maglaris. The Greek American family sold their last diner, Henry's in Burlington, earlier this year. They also owned or co-owned the Arcadia (now and previously the Parkway) in South Burlington (see p. 32), the now-shuttered Apollo in Milton and Athena's in St. Albans.

"Bill was literally the diner king of Vermont," Malone said. When he and a business partner opened the rechristened Colchester diner in January 2012, Maglaris told Seven Days the Athens would serve an extensive Greek menu, including roasted lamb plates, and the décor would nod to his homeland.

Tony Blake of V/T Commercial, who worked with the Maglarises to sell off their diners, said he believes they were the last Greek-owned diners in northern Vermont.

At the Athens Diner, the name continues to pay homage to that history, as do framed photos of the Acropolis and other historic sites hanging in the back room. A letter board sign above the counter is dedicated to Greek specialties, such as a dill-forward spanakopita made from scratch.

"I go through a lot of feta," Malone said.

Staffing constraints have dictated a five-day-a-week schedule since Malone took over, but he said last year's sales nearly matched pre-pandemic revenue, when the Athens served daily.

Malone hopes to continue building his team around the newly married cooking couple and expand hours. In the meantime, he's still working overtime to trim costs.

His latest tactic, which has already reaped rewards, is incentivizing customers to pay cash with a 4 percent discount. "Credit card processing fees are murder," he said with a grimace.

"I'm not looking to get rich," Malone said. "But like anybody else, I need to make a living."

— M.P.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

Staying on Track

Blue Benn Diner, 314 North St., Bennington, 442-5140, bluebenn.com

Avery Buck, who currently heads the kitchen at Burlington's May Day, has built his career at some the city's most acclaimed restaurants, including Hen of the Wood and the Grey Jay. But the Pownal native has a soft spot for the Blue Benn Diner.

The 31-year-old chef grew up less than 10 miles from the diner, a 1948 Silk City car. "My mom knew all the waitresses. My dad knew all the waitresses," Buck said. "You walk in there, everybody knows everybody."

As a youngster, he always begged to sit in a booth, where he'd flip through the songs on the tabletop selector of the antique Seeburg Select-O-Matic jukebox before inserting his precious quarters. "Whenever I went there with my mom, we'd play 'Brown Eyed Girl' by Van Morrison," Buck recalled.

A few years ago, Buck learned that the now-76-year-old diner had changed hands after being owned by the Monroe family for almost 50 years. On visits home, he's been relieved to find that the Blue Benn feels and tastes the same. Waitstaff ask how his family is doing; he can still play Van Morrison on the jukebox; the Country Benedict, with sausage, biscuits and gravy, is as good as he remembers.

That's exactly what owner John Getchell hopes to hear. Since taking the reins of what he called "an institution" in December 2020, his operating principle has been simple: "If it ain't broke, don't fix it," he said.

Getchell, who frequented the diner as a Bennington College student in the early '80s, reopened the pandemic-shuttered business in February 2021. The 62-year-old had owned a catering company and worked as a private chef. But he admitted that the decision to relocate from Maine to Vermont to buy and run the diner was somewhat impulsive — enabled by an inheritance that provided him with the asking price of just under $600,000.

He did do some critical due diligence before plunking down the cash. Getchell sought out many of the Blue Benn's veteran employees. "I said, 'If you guys will come back, I'll buy the diner. If you're not interested in coming back, I won't do it.'"

That roster included longtime head cook Brian Carpenter, who was trained by former co-owner Sonny Monroe and closely guards the recipe for the diner's chunky, sugared cake doughnuts. Carpenter and several kitchen staff members agreed to return, ensuring the integrity of the Blue Benn's broad, eclectic menu.

Monroe, an adventurous, self-taught cook, was known for creating dishes that went beyond diner classics. When Getchell was in college, he'd often order the Sir Benn omelette, stuffed with chicken, broccoli, mushrooms and cheddar and smothered with Hollandaise, or the spinach pesto omelette. Back in the early '80s, Getchell said, "Pesto wasn't a thing in southern Vermont."

Monroe experimented with Tex-Mex and Middle Eastern flavors and invented housemade vegetarian options such as the Nut Burger, which became a menu staple. "As far as diners go, he was a visionary," Getchell said.

Server and manager Bridget Wyman, 53, was among those who came back to work for Getchell. She had taken a 20-year hiatus after her first decade-long stint at the Blue Benn to work "a real job," as she put it, with benefits and paid time off.

Wyman, with dangly earrings and frosted hair, presides efficiently behind the counter, chatting with regulars and the many tourists, refilling coffee cups and slicing voluptuous wedges of housemade coconut cream pie.

She said the Blue Benn has largely stayed true to its past, and she credits Carpenter, in particular, with preserving the menu. "He's carried on Sonny's tradition. He knows all the recipes," Wyman said.

The deeply worn diner countertop is another visible artifact of the past. Its grooves and contours map the friction of decades of plates, cups and elbows. Getchell said he would never dream of replacing it.

The counter "gives people a sense of place and a sense of time passing," he said — just like the Blue Benn itself.

— M.P.

Long-Term Relationship

Miss Lyndonville Diner, 686 Broad St., Lyndonville, 626-9890, misslyndonvilledinervt.com

When Janet Gray Burnor's phone rang early on a winter morning in 1978, she panicked. She and her husband, Ashley Gray, were hosting a ski team for breakfast at their Miss Lyndonville Diner, and she assumed they'd overslept.

"It was the fire department," Burnor, 72, recalled. A fan hooked up to an extension cord had overheated, and the restaurant was destroyed. "We thought we were done," she said.

Almost 46 years later, Miss Lyndonville is clad in cream-colored siding rather than chrome. But it's as much a diner today as it was before the blaze, and it remains a pivotal part of its Northeast Kingdom town. Burnor believes that its longevity comes from the strength of its relationships in the community — with local residents, college students and tourists who come in for a North Country Special burger or one of 37 breakfast combos; with longtime staff; and with vendors, including the gardener who has continued to maintain the diner's vibrant landscaping, even though he's technically retired.

"It's good food, it's good service — all the mechanical stuff," Burnor said. "But it's that emotional realm that sets us apart from a lot of places."

On a recent Monday at lunchtime, after ringing up customers at the register, the farewell was "see you tomorrow" as often as it was a simple "goodbye."

When Burnor and Gray moved to town and took over the Rustic Restaurant in 1978, they chose the diner concept — and its name — as an homage to a New England tradition. Gray's father had been a partner in the Miss Florence Diner in Florence, Mass. Prior to its run as the Rustic — a truck stop with a mostly male clientele and a "bad reputation," Burnor said — the diner had been known as the Miss Lynn. Going back to the diner's roots, with a focus on affordable food, fast service and a "homestyle" atmosphere, appealed to the couple, Burnor said.

Today, the 99-seat Miss Lyndonville is the result of several additions, including a separate dining room annexed on the side. But the bones of the original Sterling diner car, built in Massachusetts in 1939, are still in evidence: Its long counter, with bolted-down stools and a shiny, silver, diamond-textured backdrop sit under exposed wooden beams that gently arch overhead. As I gazed around to take it all in, a server suddenly materialized, straw in hand.

"I thought you were trying to flag me down and figured you needed one of these," she said, sliding the paper-wrapped plastic straw between my tuna melt and tall, ice-cold glass of Pepsi.

That sort of mind reading is part of the diner's extensive training, Burnor said, which essentially boils down to "keep your eyes on your section, watch people and anticipate their needs," as she put it. It takes a certain kind of person to commit to the choreography that makes the diner's performance a success; finding enough of those people was a challenge at the start, she said, and hasn't changed much in a half-century.

Miss Lyndonville's hours haven't changed much, either, with a few exceptions. Postfire, the couple added dinner and increased service from six to seven days a week. Just before Gray died of cancer in 2005, he encouraged Burnor to cut back to dinner just twice a week, so she didn't run herself into the ground.

"There was such an uproar in the community that I felt like I shot myself in the foot," Burnor said. "I didn't do it." Instead, she closed the diner on Monday and Tuesday nights. The schedule stayed that way until the pandemic.

The most recent change is one many restaurants have made to adjust to staffing challenges: They've cut back on their hours. Burnor and daughters Kim Gaboriault and Heidi Sanborn — who have worked in the diner since they were kids and now run the dining room — brought the diner back to its original breakfast-and-lunch-only schedule, and they're now closed on Tuesdays.

"I know not being open nights is a loss to our community, and I regret it from that perspective," Burnor said.

The change might affect how many customers they see from Vermont State University's Lyndon campus, she said. They often joke that the college doesn't wake up until 11 a.m., and the diner closes at 2:30 p.m. most days.

But locals are doing their part to hold up their end of the relationship — and to bring it into the next generation. More than once, families have stopped in with their newborns on the way home from the hospital. The relationship with Miss Lyndonville literally begins in the cradle.

— J.B.

End of the Road

Springfield Diner, 363 River St., North Springfield, 886-3463, Springfield Diner on Facebook

The 81-seat Springfield Diner is big and busy enough to fool you into thinking it never left New Jersey. The rare Mahony Diner Car — the only remaining one of four produced by the short-lived Kearney, N.J., company, which operated from 1956 to 1958 — was slammed on a recent Friday at lunchtime.

"You'd better take a table before they're gone," a waitress yelled across the counter to a regular waiting by the door, holding his motorcycle helmet.

"If I wanted to get yelled at, I'd get married," he replied, sliding into the last empty booth.

A few minutes later, she chucked a leftover French fry at him on her way into the kitchen — and she had good aim.

Owner Amy Jakob didn't seem to care that fries were flying. She chuckled to herself as she watched the whole thing happen, carefully using two pie slicers to extract a wobbling piece of banana cream pie. She had bigger things on her mind.

This fall, Jakob will close the diner. Her five-year lease is up, and she couldn't reach an agreement with the landlords to renew it, she said. The diner, and another commercial building that shares its lot, are currently listed for sale together for $675,000.

They've been on the market for roughly seven months, according to Matthew Alldredge, one of three business partners who moved the diner to Springfield from the Kingston, N.Y., area to be part of a Corvette museum in 2002. They still own the property.

click to enlarge

- Jordan Barry ©️ Seven Days

- From left: A patty melt and an open-faced turkey sandwich

Jakob, 48, had hoped to keep things running. Business is good, she said. The diner, which serves breakfast and lunch five days a week, stayed open consistently through the pandemic. But like many restaurants in a tight real estate market, a sharp rise in rent means the end.

She and her now-ex-husband got divorced after signing their lease in 2019; they continued to operate the business together through that contract, she said, but now he's stepping away. This spring, Jakob — a 30-year veteran of the restaurant industry — told her landlords that she'd like to give it a go on her own.

Alldredge told Seven Days that Jakob initially communicated that she didn't want to renew the lease. At that point, the property owners hired a real estate agent to find a new tenant. "When we included the cost of the realtor, she didn't want to deal with it," Alldredge said.

Jakob said her landlords informed her via the real estate agent that they wanted to raise her rent by 50 percent, from $3,000 a month to $4,500. She proposed a compromise — a 33 percent increase — for the first two years of a new five-year contract. Alldredge disputed that claim.

"I wasn't scared to do it, but I needed time to build the business back up, to grow the staff and get weekends going again," she said. The diner has been closed on Saturdays and Sundays for the past year, since the death of an "irreplaceable" cook, Jakob said. For the remaining three years, she'd meet them at their price.

"They turned me down," she said.

The diner will remain open until the end of September, when the lease runs out. Alldredge said there are a couple of prospective tenants, and "it shouldn't be closed more than a week." Jakob will take out the equipment she and her ex added over five years — commercial freezers and refrigerators, a grill, a deli cold table — and try to sell it on Facebook Marketplace to recoup some of the thousands they spent.

Then she's leaving the state. She doesn't want to watch somebody else take over what she's built, she said. And as a single parent, she's worried she won't be able to make enough money in Vermont to support her daughter.

They'll move to Florida, where Jakob got sober in 2006, and she might open a bakery, she said. Jakob bakes everything herself at the diner, including the cranberry-orange muffins she popped in the oven while talking to a reporter. Her doughnuts — a recipe she perfected over six months and now makes three days a week — usually sell out.

Christmas cards and kids' drawings hang from the stainless-steel walls behind the counter. Jakob and two servers, two cooks and a dishwasher churn out breakfast all day, along with juicy patty melts, gravy-topped open-faced turkey sandwiches and massive, 22-ounce milkshakes for lunch. Some customers, particularly older ones, come in for both meals, she said.

"This is their social life," Jakob said. "I don't care if they tip $1 in the morning and nothing in the afternoon. At least I know they're OK."

For the next few months, anyway.

— J.B.

Put It in Park

Parkway Diner, 1696 Williston Rd., South Burlington, 540-9222, parkwaydinervt.com

In the peril-ridden restaurant ecosystem, Brian Lewis thinks diners are "the best business model, hands down." He has several points of comparison: The Fayston restaurateur owns the Filling Station, a burger-and-sushi spot in a former gas station in Middlesex; Yellow Mustard deli and Filibuster Café in Montpelier; and South Burlington's Parkway Diner. If he hadn't promised his wife he'd take a break from opening new spots, "I'd own 10 more diners," he said.

The stats seem to support Lewis' enthusiasm. The National Restaurant Association estimates that 80 percent of restaurants close within the first five years. Diners aren't exempt from that — as Jakob's Springfield Diner shows — but they do tend to persist through generations and changes in ownership. Of the 13 diners Erin McCormick Torres featured in her 2018 book Classic Diners of Vermont, only two didn't survive the pandemic: Miss Bellows Falls, which nonprofit group Rockingham for Progress is currently fundraising to redevelop, and Brattleboro's Chelsea Royal, which was purchased by a pair of local real estate businessmen last summer, the Brattleboro Reformer reported. (A third, the Diner in Middlebury, was sold to neighboring Town Hall Theater and closed in 2018.)

The Parkway had been closed for two years when Lewis, 47, took over its lease in spring 2022. He kept the interior of the 1950s Worcester Lunch Car the same — worn beige counter, red stools, original booths and all — while adding outdoor seating and updating the menu to broaden its appeal. Alongside burgers and BLTs, the diner offers Barbacoa breakfast burritos, cold brew with oat milk and boozy drinks — or "oozy drinks," as the overhead menu board proclaimed on a recent Tuesday morning — including mimosas, Bloody Marys, Fiddlehead IPA and White Claw.

The dishes — and their high-for-a-diner prices, hitting $19 for chicken-fried steak — are similar to those at Filibuster, Lewis' newest breakfast-and-lunch spot, which opened on Montpelier's State Street in January.

Shortly after he signed the lease for the Parkway in March 2022, Lewis told Seven Days that all-time-high labor and product costs would mean a price hike from the what the diner's previous owner had been charging. "You're gonna get what you pay for," Lewis said. The kitchen makes all the bread and English muffins using King Arthur Baking flour, and the dairy and maple syrup are local, Lewis explained. The toast and eggs, biscuits and gravy, waffles, and hash fit the classic diner bill. It's not diner cosplay, just more expensive.

Even with just 42 seats to Filibuster's 76 (when the latter's patio is open), the diner "outperforms Filibuster every single day" in total sales, Lewis said.

Sure, the Parkway has been a staple on busy Williston Road near the Patrick Leahy Burlington International Airport for 70 years. But its success comes from its efficiency, Lewis said.

Servers at the Parkway can practically pivot on the spot to get food from the kitchen window to their customers, rather than traipsing through Filibuster's spacious dining room. The diner's food hits the counter in 10 to 12 minutes, he said, and tables turn in 30 minutes; Filibuster's elegant setting and plush banquettes encourage customers to linger. The diner needs half the staff of its larger counterpart and costs less to heat.

"The people who created diners really thought about what they were doing," Lewis said.

Seventy years in, it's not just the nostalgia that keeps the Parkway around. These all-American diners keep on chugging.

— J.B.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Order Up | What Vermont's classic American diners tell us about the current state of restaurants"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Authors

Jordan Barry

Bio:

Jordan Barry is a food writer at Seven Days. She holds a master’s degree in food studies and previously produced podcasts about bread and beverages.

Jordan Barry is a food writer at Seven Days. She holds a master’s degree in food studies and previously produced podcasts about bread and beverages.

Melissa Pasanen

Bio:

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Latest in Category

Related Locations

-

Athens Diner

- 46 Highpoint Ctr., Colchester Chittenden County VT 05446

- 44.50367;-73.18261

-

802-655-3455

802-655-3455

- www.facebook.com…

-

Birdseye Diner

- 590 Main St., Castleton Rutland/Killington VT 05701

- 43.61210;-73.17751

-

802-468-5817

802-468-5817

- www.birdseyediner.com…

-

Blue Benn Diner

- 314 North St., Bennington Manchester/Bennington VT 05201

- 42.88527;-73.19780

-

802-442-5140

802-442-5140

- www.facebook.com…

-

Martha's Diner

- 585 Route 5, Coventry Northeast Kingdom VT 05825

- 44.81323;-72.21862

-

802-754-6800

802-754-6800

- www.facebook.com…

-

Miss Lyndonville Diner

- 686 Broad St., Lyndonville Northeast Kingdom VT 05851

- 44.52935;-72.00100

-

802-626-9890

802-626-9890

- www.facebook.com…

-

Parkway Diner

- 1696 Williston Rd., South Burlington Chittenden County VT 05403

- 44.46396;-73.15706

-

802-652-1155

802-652-1155

- www.parkwaydinervt.com…

-

Springfield Diner

- 363 River St., North Springfield Brattleboro/Okemo Valley VT 05150

- 43.32137;-72.50618

-

802-886-3463

802-886-3463

- www.facebook.com…

find, follow, fan us: