Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

The Ballad of Tom Banjo, Vermont's 'Vagabond' Storyteller

From folk songs to his colorful cranky shows, Tom Azarian, aka Tom Banjo, has achieved something like folk legend status in Vermont. His new album may be his last.

Published October 2, 2024 at 10:00 a.m.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

Ballads played by wandering troubadours, sung around campfires or harmonized on front porches have told our stories since ancient times. Grand or small, romantic or sorrowful, from the medieval lamentation "Greensleeves" to "Alice's Restaurant," tales set to music have been passed down from one generation to the next. Now, in an era when we tell stories in 5K ultra-high definition with surround sound — or on the phone in our pocket — the storytelling traditions of the ballad can feel like an art form out of time, its practitioners better suited to an earlier age.

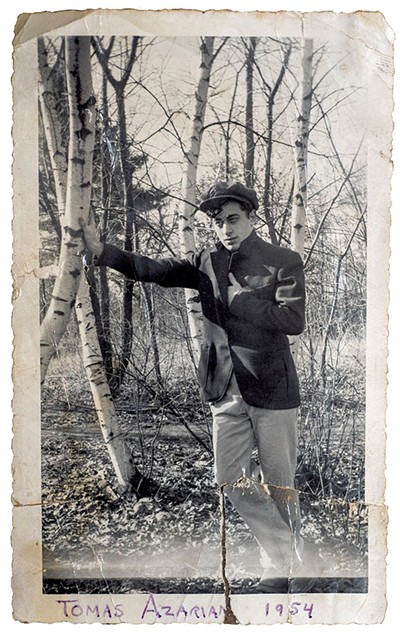

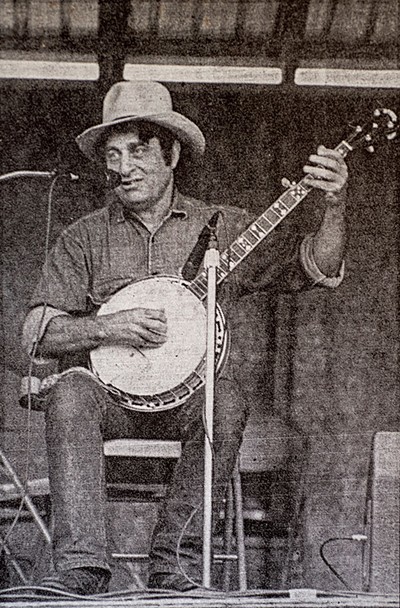

But for younger generations of uninitiated Vermonters, those traditions are on full display in the work and biography of storyteller-musician Tom Banjo — or Tom Azarian, if you must. While not quite older than the hills, the diminutive 88-year-old balladeer is a living encyclopedia of songs and tales from the American folk canon, collected over a lifetime as an antiestablishment storyteller who has used his art to entertain, protest injustice, preserve vanishing folk ways or just earn some beer money.

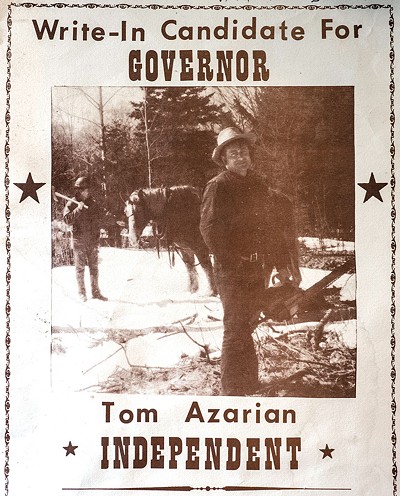

As a performer, he's been a fixture on Vermont stages, large and small, since the early 1960s, though you're just as likely to have seen him busking on street corners from Burlington to Montpelier. He and his five-string banjo have been a common sight at political rallies protesting one injustice or another. In the 1980s, he even made at least a half-serious bid for governor.

Azarian has never tasted fame or fortune, but his youthful musical wanderings placed him alongside the likes of Judy Collins and Taj Mahal long before they became household names. His closest brush with renown is being name-checked in a Grateful Dead song — probably.

But in Vermont Azarian has achieved something like folk legend status, thanks to his accomplished banjo work and a reedy, high-lonesome tenor that seems to have drifted in from the mountains of Appalachia. He embarked on a bohemian rural life here years before the arrival of hippies and back-to-the-landers, but his kinship with them — especially over populist politics, a shared mistrust of authority and, of course, music — cemented the Tom Banjo persona, as did his working-class background.

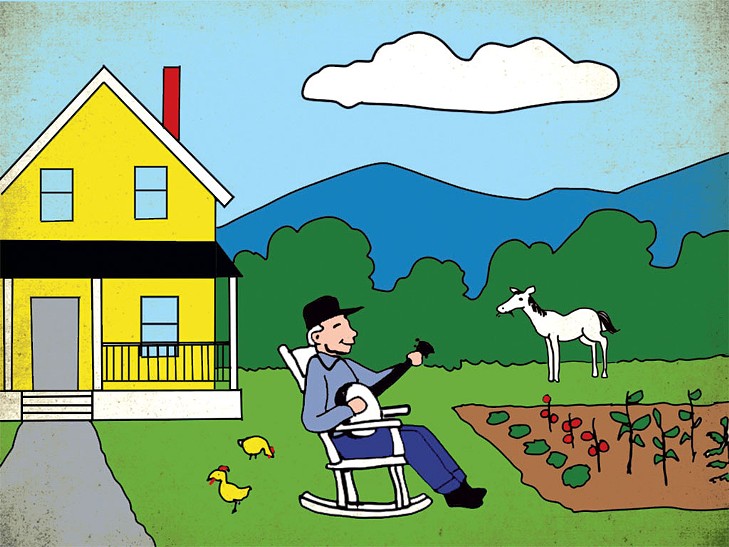

Those countercultural leanings and love of storytelling also show up in what are probably Azarian's best-known creations, his offbeat "Cranky Shows," in which he sings the narration of tales told in cartoon form on hand-painted paper scrolls that roll past the viewer's gaze like some old-timey movie contraption. (Parts of this very story are told and illustrated in the style of an Azarian cranky show.)

He's performed that brand of eccentric homemade theater — a kind of folk art all its own — at nightclubs, theaters and birthday parties from Burlington to Austin, Texas. And he still does, at least when he can get a ride. He'll be at Bread and Puppet Theater in Glover this Saturday, October 6.

Though the peak of his make-do performing career is largely in the past, he's not done creating. This week, about a month before his 89th birthday, Azarian will put out a new Tom Banjo album, Music of the Common People: American Folk Songs, Labor Songs, Ballads, and Unauthorized Opinions. Produced by Burlington musician and recording engineer Peg Tassey over the past year and a half, the record is quite possibly the last collection of entirely new recordings he'll make.

It's tempting to suggest that as Azarian nears 90 years, he is contemplating his legacy by putting more of his music to tape. Tom Banjo has little use for such speculation.

"I'm not that important," he said, blue eyes twinkling — an Azarian cue that there's more to the story. "I'm not a professional musician. I never have been and never will be."

That's ... mostly true. As in many of Azarian's best yarns, fact and fiction have a tendency to fold into one another when it serves the story. That, after all, is the way of old folk ballads: They twist and change through years and retellings — keeping important truths alive. The truth is that Vermont wouldn't be Vermont without unsung folk heroes like Tom Banjo, whose own long ballad has unspooled before our eyes with deep artistic commitment, lots of color and a healthy dash of humor, like one of his cranky shows.

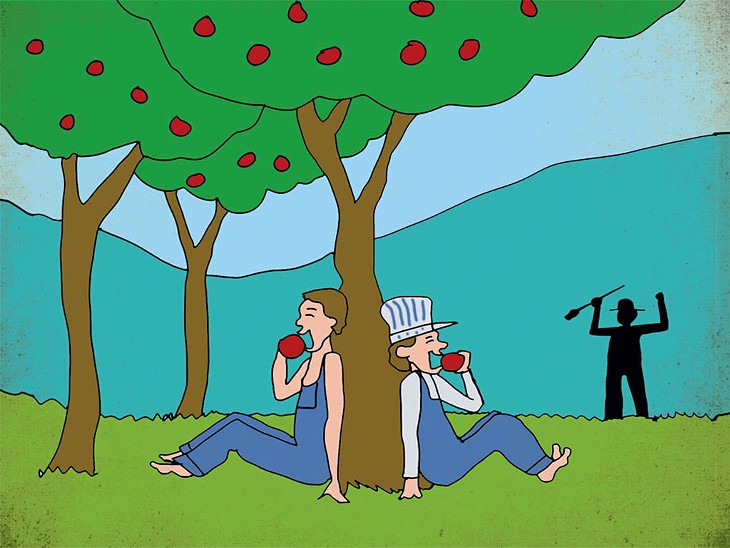

How D'Ya Like Them Apples?

Lyrics by Dan Bolles

Art by Robert Waldo Brunelle Jr.

One sunny day in western Mass.

in 1945,

young Tom Banjo roamed the countryside,

feelin' glad to be alive.

Tom and his brother came upon

an apple orchard-o!

So down the hill they scrambled,

a-poachin' they did go.

Sweet and ripe like candy,

the apples did delight.

That is, until Old Farmer John

gave those boys quite a fright.

A-howlin' he did wave a stick,

Tom swore it was a broom.

Right up until Old John took aim

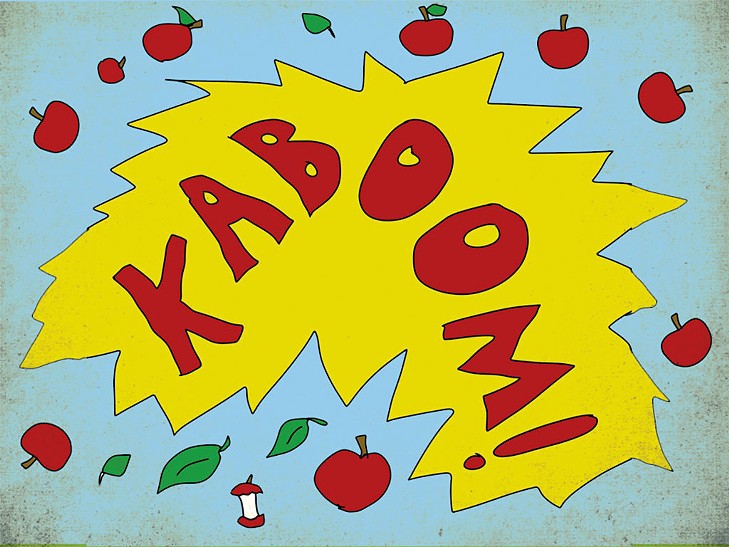

and that broomstick went...

No, an irate apple farmer didn't shoot Azarian and his brother for stealing apples when they were kids. But a couple of farmworkers did shoot at them, according to Azarian. Whether a warning shot or poor aim explains the miss, Azarian isn't sure. "But I remember the pitter-patter of rock salt hitting those leaves," he said. "And o' course, we ran like hell."

As he spoke, Azarian was seated at the head of the long wooden kitchen table of the rustic farmhouse in Calais where he lives with his sons Jesse and Tim; Tim's wife, Wilaiwan, who owns the Montpelier Thai restaurant Wilaiwan's Kitchen; and two grandchildren. A battered black engineer's camp rested above his craggy face, shading eyes the same color of his faded denim shirt and jeans. When Azarian laughs or smiles, which is often, gleaming dentures brighten his weathered features.

His banjo was in another room, but an old guitar rested on a love seat behind him, flanked by shelves stuffed with books on two of his favorite subjects: music and history. His third favorite preoccupation lay outside the bay window, the expansive gardens he still tends with his ex-wife, Mary, who lives down the road.

With its low ceilings and exposed wooden beams, Azarian's kitchen has the warm, welcoming feel of a hobbit hole; the lush grounds of the family's homestead are something like the idyllic Shire. It's an inviting setting in which to hear good stories.

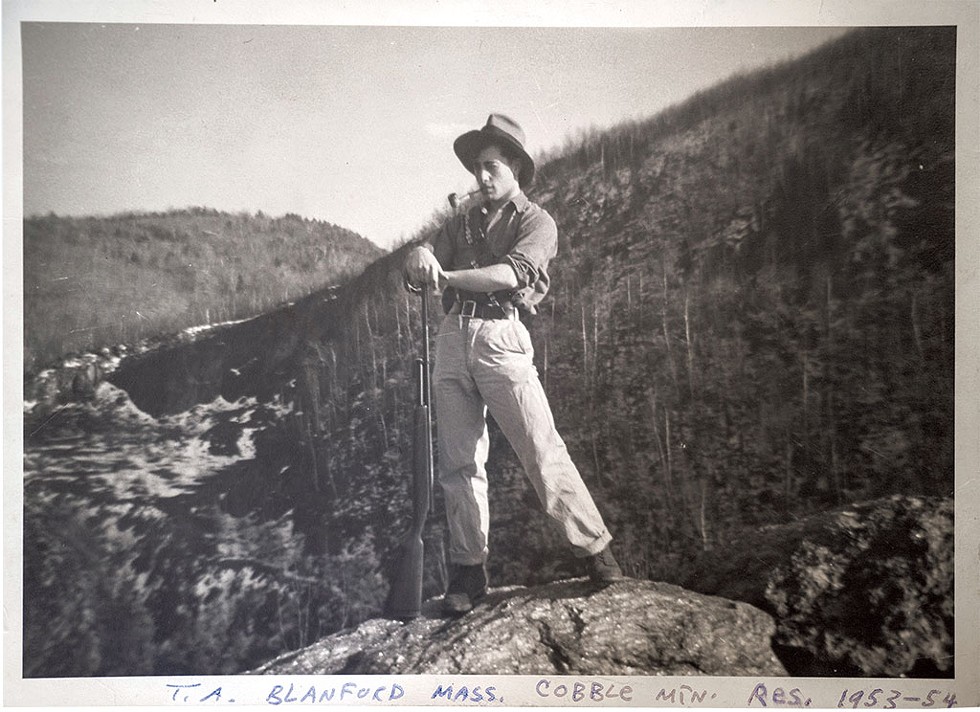

While dodging rock salt was a rare occurrence for Azarian and his brother and sister, theirs was still a hardscrabble upbringing in the shadow of the Berkshires. Azarian was born in Westfield, Mass., in 1935, the middle of the Great Depression.

"We were those kids you probably read about who were malnourished and hungry because we didn't get enough to eat and there was no welfare," he said in a lilting rural twang that comes and goes as he speaks.

To listen to Azarian spin out his biography is to see glimpses of the folksy Tom Banjo persona that is both a bit of theater and a genuine reflection of who he is. He is warm and funny — and occasionally a bit off-color — and has a not-unpleasant habit of meandering, even when answering direct questions.

Azarian may pause at times to summon a name or year, but he recalls most details with remarkable clarity. His tales are delivered with such charm that they can feel both practiced from decades of performance and spontaneous, as if they just occurred to him, just for you.

His maternal grandparents fled the Armenian massacre in the mid-1890s, landing in the U.S. in 1901. His father came here after surviving the Armenian genocide of 1915. His parents worked factory jobs that paid little and often fell behind on rent. The family was evicted when Azarian was 6 or 7 and landed on the edge of town in what he calls "a hermit shack." The hovel was heated with kerosene when they could afford the fuel. His mother and younger sister slept on the only bed. Azarian, his older brother and father all slept on couches — a habit Azarian never quite shook.

"I didn't sleep in a bed until I was married," he said.

What the Azarian home lacked in food, heat and beds, it made up for in music. His father played violin and mandolin, and his brother "played a mean fiddle and guitar," Azarian recalled. On Saturday nights, they'd listen to broadcasts of "The Grand Ole Opry," the country music radio show beamed in from Nashville. That's where, one night in 1946 or 1947, he heard the banjo for the first time, played by singer and comedian Uncle Dave Macon.

"It blew my mind because it sounded unlike any other instrument," Azarian said. "It just grabbed ahold of me, and I became addicted to that sound. And I told myself, I gotta get a banjo."

By 1951, Azarian had left school with an eighth-grade education and started working at a machine shop alongside his father, then at a greeting-card factory with his mom. Eventually, he saved up enough to buy a $35 Kay banjo from the Sears catalog.

"Everywhere I went, I played that banjo," he said. "I just couldn't stop."

Azarian and his friends, good singers all, mostly covered old traditional tunes learned at neighborhood parties. "We didn't know they were folk songs," he said. When they chose newer songs, they were especially keen on the warblings of a hotshot young country singer named Hank Williams.

In his late teens and early twenties, Azarian took a cue from Williams and hit the lost highway himself, rambling to bigger towns and cities nearby to catch live music and play when he could. One night at a coffeehouse in Springfield, Mass., he met a folk musician named Burt Porter.

"And that's when this whole Tom Banjo thing happened," he said.

Where the Time Goes

By the late 1950s, folk music was in the midst of a full-blown revival, particularly on college campuses, where the countercultural ideals that would help shape the 1960s were taking root. Porter was a grad student at the University of Connecticut and immersed in the folk scene there. He and Azarian started playing at coffeehouses, parties and on the campus radio station.

"I didn't think I'd much care for college," Azarian said. "I thought it was just for rich kids and loud-mouthed frat boys. But I met a lot of nice people there."

Among them was a promising young singer named Judy Collins. Porter and Azarian played a show at the university with Collins, who invited the duo to share a bill with her at the Bitter End, the famed New York City folk and rock venue. They did, "and that was the last time I saw her," Azarian said of Collins, who would become a Grammy-winning folk-music icon. "After that she got famous."

While fame may have eluded Azarian, he did manage to leave an impression at UConn, where he stood out, partly for his shabby attire — a blue-collar workman style that he hasn't veered from much in the past 70 years. And the banjo wasn't an especially common instrument, so those who played it were rare and often in demand.

Azarian became known for his itinerant ways. He would often show up out of the blue, stay for a few days or weeks, and then disappear as abruptly as he'd arrived, sometimes home, sometimes to seek out music in other towns.

"They thought of me as some kind of vagabond," Azarian said. The musicians he befriended knew him as Tom, but no one knew his last name.

"They'd just say 'Who's that guy, you know, with the old clothes, who keeps showing up playing the banjo?'" he recalled. "'You know, that Tom banjo guy.'"

The name stuck.

After his UConn experience, he was drawn to college towns because students, he said, "were the first ones coming on to American folk history and music." That included stints in the storied Harvard Square coffeehouse scene in Cambridge, Mass., where he befriended the likes of Taj Mahal, who was still a relative unknown.

One Saturday night, Azarian was playing at a basement jam session at Smith College in Northampton, Mass. In the crowd was a student named Mary. During a break, she introduced herself. Then she asked him, "What do you know about socialists?"

The two didn't hit it off right away. Although Mary was smitten with Azarian — "His voice was so mesmerizing," she said — he felt unsure. She was well educated and came from an upstanding family in Virginia, while he was a "wayward bum," Azarian said.

"He did everything he could to evade me," Mary said.

Eventually, though, he softened.

"She was open to everything, curious," he recalled. "She liked the same kind of music I like. She liked old things. She liked flowers and animals.

"I says, Gee, maybe this is the girl I've been looking for all my life."

Mary's conservative parents, he said, were unimpressed by her scruffy-looking boyfriend. "He looks like a gangster," Mary's father groused. To which she shot back, "Yeah, and he's a communist, too!"

As the relationship bloomed and the couple began to consider a future together, Azarian revealed his desire to move to Vermont. He wanted to own a farm with horses and cows and live off the land. She, meanwhile, was a double major in art history and medicine who was considering an MFA at Yale or a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh. But she was intrigued by Azarian's plan.

"We'll have no electricity," he cautioned. "We'll have kerosene lamps and use burlap bags for curtains."

Her response?

"She was all for it."

Goin' to the Country

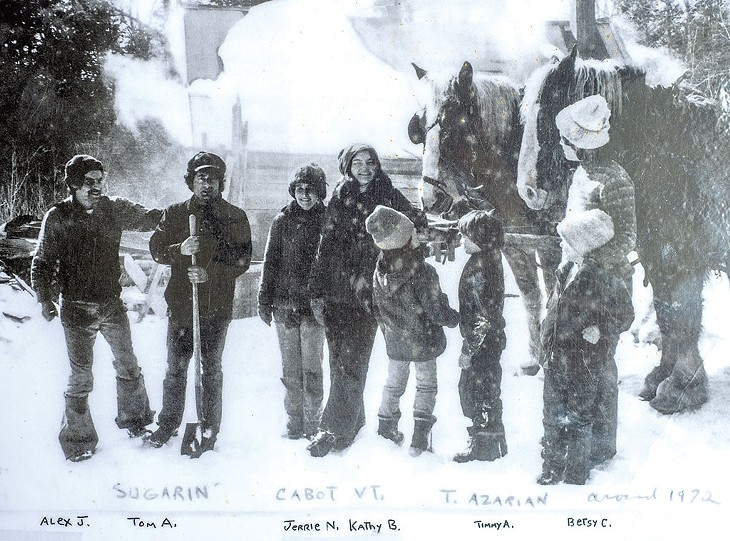

Azarian and a very pregnant Mary arrived in Cabot in March 1963. They had to snowshoe into their new home. As envisioned, they started a 19th century-style farm with cows, chickens and horses. The couple grew crops in the summer and sugared in the spring. They did have electricity, but Azarian worked his fields with oxen and collected maple sap with buckets, not lines. The Azarians raised three boys, Ethan, Jesse and Tim.

While they lived mostly off what they grew or bartered, both occasionally took on the odd "shit job," to make ends meet, Azarian said. His wily, independent streak no doubt endeared him to his neighbors in central Vermont, which, as the '60s wore on, was home to increasing numbers of hippies and back-to-the-landers drawn to the Green Mountains in search of a rural utopia of free love, psychedelics and communal living.

Azarian said he never went in for all that — he just wanted to live simply. But in an area as sparsely populated as central Vermont, people of similar mindsets were bound to find each other. He was soon playing his banjo with a new generation of Vermont folk musicians carried in with the hippie tide.

Azarian was a regular at the Craftsbury Banjo Contest and the Craftsbury Old Time Fiddlers Contest. Those annual festivals drew top players from around the country until the mid-1980s, when they were shut down for growing too rowdy. Every year at festival time and at holidays, the Azarians hosted dayslong parties at their homestead that would become the stuff of local lore. Musicians from all over New England would join in jam sessions that stretched into the early morning.

"It was magic for me to stay up all night and listen to these people, my parents and my dad's friends, playing banjos and fiddles," said son Ethan, who, like his siblings, is now a musician and artist.

Azarian gigged locally with various groups and performed solo to earn extra money. He was hired frequently by the Vermont Council on the Arts — now the Vermont Arts Council — to play shows at schools and other events.

His most regular collaborator in those days was his old UConn buddy Burt Porter, who had also landed in Vermont. The two often performed at the Bread and Puppet Theater, the famed artist collective in Glover. In fact, Bread and Puppet is where Azarian was schooled in a long-standing art form known as cranky theater, by a member of the troupe named George Konoff. When Konoff left in the '70s, he bequeathed his cranky box to Azarian.

Azarian and Porter, who was a fine fiddler and singer, were a formidable duo and found modest success around Vermont. In 1972, at the urging of a Morrisville minister who thought they had potential, the pair decided to cut a record and approached Bill Schubart and his half-brother, Mike Couture, who co-owned the influential folk music label Philo Records in North Ferrisburgh.

Philo was home to some of the great folk acts of the era, among them Dave Van Ronk, Mary McCaslin and Utah Phillips. Although Schubart and Couture agreed that Azarian and Porter had promise, their timing was bad. Philo typically covered all of the expenses, Schubart explained, including recording, distribution and promotion. But at the time, it lacked the money to back an unknown act. Schubart suggested instead that the duo record on Philo's sister label, Fretless, which used a hybrid publishing model in which the artist paid some of the expenses, while the label distributed the record.

That album, titled Burt Porter and Tom Azarian, was released the following year, in 1973. It didn't make much of a splash but, according to Schubart, contains some performances worth revisiting — if you can find it.

Schubart maintains that, in particular, "Queen Jane," Azarian's version of the Francis James Child ballad "The Death of Queen Jane" is among the best he's ever heard.

"It took my breath away," Schubart said. "After they left, I must have sat in the studio with a fifth of bourbon and listened to it 10 times."

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

Crank Calling

In 1982, Azarian and Mary separated. She moved with the kids to an old farmhouse on a long dirt road in Calais while he stayed in Cabot.

Two years later, in 1984, Azarian made an unsuccessful run for Vermont governor as an independent. It's unclear how serious he was, but he was invited to at least one radio debate, where, he jokingly recalled, he was able to restrain himself from promising to overthrow the government. While he's often thought of as a socialist, his political platform swung from no-nukes to anti-tax, at least when it came to working family farms.

By then, Mary, a children's book illustrator and woodcut artist, had won a prestigious Caldecott Medal for her work. And he was, well, Tom Banjo — happily underemployed, content to play banjo, tend his gardens and drink beer.

In the late 1980s, Mary sold the Cabot farm, and Azarian moved into the house in Calais, though they remained separated. In 1995, as Azarian put it, "she threw me out." It wasn't really a divorce, since the two were never legally married, even though Mary took Azarian as her name and still uses it.

Azarian moved to Burlington, landing in a low-income housing co-op on Pearl Street, a house that stood out for the gigantic sunflowers that he planted and tended. To help pay his rent, he put his gardening expertise to use at farms in the Intervale.

He soon befriended a fellow co-op resident, a young Connecticut transplant named Patrick Johnson. "We ended up on the same porch," is how Johnson explains it.

Before long, they ended up busking for beer money together, joining forces in making the cranky show a cultural fixture.

The cranky show is a two-person operation. Its centerpiece is a large, handmade wooden box with a rectangular opening in the front. Inside is a long reel of butcher paper, on which Azarian has illustrated his stories — three stories to a scroll. The scroll is turned by a pair of wooden hand cranks on top — hence "cranky show" — that move the images across the opening, like a makeshift movie screen.

Because Azarian is busy singing and playing his banjo, he needs a helper to operate the cranks. His kids and grandkids have often done the job over the years. But during the time Azarian was in Burlington, that person was Johnson.

"It's not as easy as it looks," Johnson said.

For one thing, timing is everything. The scroll should neither speed ahead of Azarian's singing nor fall behind, lest the images and music fall out of sync. Given Azarian's tendency to take liberties with tempo and his habit of altering verses on the fly, a successful cranky operator needs to be innately attuned to Azarian. Sometimes even those closest to him find it all too much.

"At a certain point I had to stop doing it, or we would have killed each other," his son Ethan said.

Johnson, a carpenter, built the cranky box Azarian used in Burlington — he still performs with it when he's in town. Azarian's son Tim built another that he uses elsewhere. Johnson called mastering the device "going to cranky college," and has been cranking for Azarian for almost 30 years, often for lucrative tips on the Church Street Marketplace. The two were also sometimes hired for children's birthday parties. They performed many of their cranky shows at Radio Bean, the Burlington café and music venue. For many years, Azarian was a near-daily fixture there — leaning on the bar, sipping a beer — until he left Burlington in 2019. And his cranky shows, including some risqué versions, have remained a staple of the venue's calendar for just as long.

Most of Azarian's cranky show stories are based on old songs, such as "One Meatball," which was popularized by singer Josh White in the 1940s but has roots in the Tin Pan Alley era. And there are a handful of blue crankies, which often follow a similar format as the dirty "Man from Nantucket" limericks but set to music.

"There's a room in everybody's brain that they didn't know was there until Azarian opens it with his cranky show," Radio Bean owner Lee Anderson said. "It's so folky and touches on so many things: It's Marxist communist worker stuff, antiestablishment politics.

"But also, his cartoons are amazing," Anderson went on. "So well done and funny and historic."

Azarian prefers to do his cranky shows at night. His contribution to the evolution of cranky theater was adding a light bulb to the box, which illuminates the scroll. That electrifying development initially horrified Bread and Puppet founder Peter Schumann, though Azarian said his old, technology-averse friend has since softened.

"I think he eventually forgave me," he said.

Azarian's classic cartooning style is influenced by "Mutt and Jeff" and other comic strips from his childhood. But there's also a subversive edge that recalls the artwork of outsider folk musician Michael Hurley, a Vermont contemporary in the 1970s and '80s.

Anderson said part of the appeal of Azarian's cranky shows is the historical context he often provides before each tale. He'll talk about where certain songs might have originated and how they've changed — or how he's changed them.

"He keeps that bard tradition alive," Anderson said.

Johnson suggested that a distinctly Azarian sensibility emerges alongside themes of power disparity and inequality.

"He has characters that always show up in his work," Johnson said. Azarian never appears as a character in the cartoons, but Johnson noted a striking similarity between the singer and certain archetypes that do. "There's always this poor, downtrodden guy, like in 'One Meatball,'" he said. "And [Azarian] draws a lot of strong females and sort of weak, mousy men. Does art imitate life?"

It might.

One day, Azarian mentioned to Johnson that he thought he had been name-dropped in the 1969 Grateful Dead song "Mountains of the Moon." That song, written by Robert Hunter and Jerry Garcia, contains this verse:

Hey, Tom Banjo

It's time to matter

The earth will see you on through this time

The earth will see you on through this time

Down by the water, the marsh king's daughter, did you know

Clothed in tatters, always will be, Tom where did you go?

For years, folks had asked Azarian if he was the Tom Banjo from the Grateful Dead song — or if that's where he had taken the stage name. He'd often thought it could be him but also had heard suggestions that the figure in question was Tom Paley from the New Lost City Ramblers or, given the song's fantasy bent, Tom Bombadil from J.R.R. Tolkien's novel The Fellowship of the Ring. Azarian asked Johnson to do some internet sleuthing because he didn't use computers himself (and still doesn't).

It turns out that Hunter, the songwriter, was a student at UConn in 1958 and 1959, the same years Azarian was bumming around the college. Like Azarian, Hunter was a fixture in the folk scene there, so it's likely their paths crossed at some point, even if they never formally met.

That hardly amounts to confirmation. But that last line in the verse could describe a certain itinerant banjo player: "Clothed in tatters, always will be, Tom where did you go?"

Azarian has an answer for that one: "I went to Vermont."

The Ballad of Tom Banjo

Lyrics by Dan Bolles

Art by Robert Waldo Brunelle Jr.

Old Tom Banjo

lived on a farm,

pluckin' his strings,

never meanin' no harm.

He played old songs

and he played 'em his way,

pickin' and a-singin'

each and every day.

Tom did ramble,

Tom did roam.

But when he played his banjo,

he always felt at home.

Never made no money,

rarely had a job,

but he's the richest man

in the whole of Vermont.

Old Tom Banjo

plays his music still.

The ballad of Tom Banjo

echoes through the hills.

Azarian claims he didn't particularly want to make the new Tom Banjo record. That said, he also didn't require much convincing. When asked why it was important to record it, especially at his age, he replied, with that telltale twinkle, "Peg was the instigator."

Peg Tassey, a Burlington musician who's been rocking and rolling around Vermont since the 1980s, has also developed a growing reputation as a producer who collects wandering musical souls.

Her last big project was Montpelier vocalist Miriam Bernardo's 2019 debut record, Songs From the Well. Bernardo had long been regarded as one of the state's finest vocalists but had never made a solo album until Tassey pushed her to do it.

Tassey approached Azarian about recording at her new Emotionoise Studio after she saw him play last year at the Whammy Bar, a tiny general store-slash-music venue at Maple Corner in Calais. She'd known the Azarians for more than 40 years and is a friend and musical contemporary of their son Ethan. Ethan Azarian had cautioned her that his dad was likely more comfortable playing at farmers markets than amid the high-tech gizmos of a modern recording studio. But to everyone's surprise, the old man agreed to do the record.

Over the next year or so, Azarian would bum a ride from the remote family homestead in Calais to Montpelier, where he'd catch a bus to Burlington and record for a day or two at a time with Tassey. He stayed nights with his friend Johnson, who has a guest room with a bed. Azarian, however, preferred to sleep on the couch.

The project tested Azarian's mettle as a musician and singer. He has twice had surgery on his hands to combat carpal tunnel syndrome, which has sapped some of his dexterity. But even in his prime, he was never the fastest or flashiest player. His distinctive style, rooted in old-time rather than bluegrass, relies more on melody, frailing and rhythmic strumming than fiery licks. And he still plays well enough to accompany himself on the old folk tunes and ballads that comprise Music of the Common People.

While Azarian says he can't hit the high notes like he used to, the weathering effect of age has lent his keening voice more gravitas. As such, his new record is not only a celebration of a beloved Vermont musician, it serves as a historical artifact.

On the opening track, "Goodbye Girls," Azarian spends a full minute explaining the origins of the old New England folk song and reveals that he's written in verses of his own that keep with its theme. That practice also follows folk tradition, in which performers would often adapt lyrics or write new ones if they didn't know the original. "Goodbye Girls" is one of several traditional songs on the album featuring Azarian's own lyrical additions.

"His music is learned in the way of the genuine oral tradition," said Mark Greenberg, a central Vermont educator, musician and producer who has known Azarian since the 1970s. "Tom's the real deal."

Another central Vermont friend, Montpelier musician and storyteller Tim Jennings, believes that Azarian's music and art is a prime example of 20th-century Vermont folk art. "Tom founded himself on legendary figures," Jennings said, "and he is a legendary figure."

If fame has eluded Azarian, Jennings offered, it is because he never really sought to capture it.

"He hasn't ever tried to become respectable," Jennings said. "And as a result, he has not been taken seriously by people who really should have taken him seriously and given him money."

If that bothers Azarian, you won't hear him say it. He's busy looking ahead. In addition to the new record, Azarian and his son Tim plan to release a collection of songs that Azarian recorded at Burlington's White Crow Studios in 1988, along with a handful of new tracks.

The efforts cement the octogenarian's standing in Vermont. Yet the only legacy he seems truly concerned with is the musical inheritance he is leaving to his children and grandchildren, musicians and artists all. Granddaughter Aliza, 17, in particular, has stirred talk that she may be the next musical Azarian to make waves in Vermont.

Although Azarian allows that "it would have been nice" to make a living solely making music and art, "I never had the connections." With that twinkle, he added, "Most of my connections are bummy guys like me who drink beer."

At least that's the story he'll tell.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

Music of the Common People: American Folk Songs, Labor Songs, Ballads, and Unauthorized Opinions is available at tombanjo.bandcamp.com. Tom Banjo performs at Bread and Puppet Theater in Glover on Saturday, October 6, at 2 p.m. breadandpuppet.org

The original print version of this article was headlined "The Ballad of Tom Banjo | From folk songs to cranky shows, Tom Azarian is Vermont's "vagabond" storyteller"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Dan Bolles

Bio:

Dan Bolles is the culture coeditor at Seven Days'. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

Dan Bolles is the culture coeditor at Seven Days'. He has received numerous state, regional and national awards for his coverage of the arts, music, sports and culture. He loves dogs, dark beer and the Boston Red Sox.

find, follow, fan us: