Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Burlingtonians Adapt as Drug Use and Safety Concerns Rise

Homelessness and urban problems will likely remain prominent in the Queen City for some time. Businesses and residents are seeking ways forward.

Published August 14, 2024 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated August 20, 2024 at 9:51 p.m.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

The economic engine of Vermont, the Queen City has never been spared from homelessness, addiction and crime, but the challenges have worsened in recent years. More than 300 people are living rough in the greater Burlington area, more than ever before. Record overdose rates, fueled by fentanyl, have overwhelmed first responders.

"I'm not going anywhere near downtown without my Taser," a 63-year-old woman told Seven Days, referring to a handheld device that shocks a person on contact. She was struck in the back of her head by a woman one May evening on South Winooski Avenue, where, earlier that day, an 82-year-old man had been assaulted.

People living outside share these safety concerns, too. Rebecca, who didn't provide a last name, recounted being kicked and urinated on while sleeping recently.

"In the old days, nobody would do that," Rebecca said. "I feel very concerned for my safety. I feel like somebody could really hurt me."

Reality has set in: There are no quick solutions. While Burlington pursues long-term ones, residents and workers are learning to live with the new normal.

City leaders are creating programs and positions to help people on the margins. Clergy are praying about how they can both be charitable and keep their congregants safe. With cops shorthanded, businesses are taking matters of theft into their own hands. Newly elected Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak, who ran on a platform of community safety, said on Monday that the city will focus on hot spots as her administration continues to strategize.

The mayor recently convened a team of advisers to help address Burlington's woes. Most of their suggestions are short-term steps, but other parts of the mayor's plan will take years to bear fruit.

"There's no one thing that would solve any of this, because it would have been done already," she said. "Continuing to adapt is one of the things that we're going to need to do."

Several entities are working to solve these problems. The nonprofit Howard Center, for instance, runs a needle exchange. For more than 20 years, its Street Outreach team has helped people in mental health crises. The Burlington Business Association advocates for merchants worried about crime and disorder. Volunteers serve meals and provide social opportunities for the city's most vulnerable.

The groups' interests and approaches don't always align, but they share the same goal: to keep Burlington the same safe, welcoming and weird city it's always been.

Burlington isn't alone in its challenges. In June, 300 people attended a forum in St. Albans to discuss shoplifting and drug activity. A similar event in Morristown in January drew 100 people after a rash of retail thefts. Homeless encampments, of course, exist in Vermont outside of Burlington, too.

State lawmakers have responded by passing stronger drug-dealing laws and increasing penalties for retail theft. There are also more compassionate responses in the pipeline, such as plans to open the state's first-ever overdose-prevention center in Burlington and build hundreds of housing units, many for formerly homeless people. A drop-in mental health clinic is expected to open in the Queen City this fall.

These approaches may make a difference in time, but for now, Burlington is in the thick of it. Its people are starting to adapt.

Special Teams

Amid the bustle of tourists on the Church Street Marketplace one steamy July afternoon, a man on a bench was turning blue. His head lolled back, and his arms were splayed as if welcoming the emergency medical technicians rushing his way. Kneeling at the man's side, EMTs injected medication into his arm, and onlookers waited for it to take effect.

The man came to in seconds. He stood up, his eyes wide and searching as if he didn't know where he was or how he'd gotten there. Perhaps he didn't.

"We're gonna help you, man," an EMT said calmly, rubbing his arm. "We're the fire department."

The crew had already responded to eight similar calls that day, and it was only 4 p.m.

The drug and homelessness crises have put significant strain on virtually every arm of city government. Workers who investigate housing code violations are spending their mornings picking up discarded needles. Librarians are banning disruptive patrons from the stacks. Park rangers are connecting unhoused people to social services.

But perhaps none has a closer view of the city's challenges than emergency responders. To adjust to the new reality, they're being more thoughtful about who they send to calls. Instead of a fire engine, a two-person team in a pickup is often dispatched to suspected overdoses. Social workers, not just armed police officers, are helping people in a mental health crisis.

"How do we make sure Burlington's a modern-day city that can rise to the occasion of the realities of living with modern-day city challenges?" Mayor Mulvaney-Stanak asked. "We are trying things. We are being proactive."

A surge in emergency calls coincided with a shrinking of Burlington police ranks. In 2021, Police Chief Jon Murad created a "priority response plan," which says when two or fewer cops are available, they'll only show up for the most serious calls, such as robbery and assault. The system is still in effect, but a cadre of civilians is helping to fill the gap for less serious incidents.

Social workers known as "community support liaisons" visit encampments, bring people to appointments and hang out at King Street Laundry on Wednesdays, when unhoused people can wash their clothes for free.

"Community service officers," who wear uniforms but not guns, take complaints about noise, property damage and other quality-of-life concerns. They also serve subpoenas, direct traffic at crash scenes and log foot patrols — more than 600 of them just this year, mostly on Church Street. This year, they've handled 13 percent of dispatched emergency calls.

On a recent afternoon, Lacey Smith and Anna Wageling, civilians who both help run a crisis-intervention program under the police department, walked Church Street, toting a fanny pack stuffed with snacks and Gatorade powder to hand out. Back at their office at police headquarters, they keep a filing cabinet with clothes, toiletries and even kids' toys. A handwritten chart on a whiteboard keeps track of where the team has checked in that day.

"We've gained a lot of trust with folks who are wary of any type of authority figure," Wageling said. "We've been able to really bridge that and show ... we're really just here to help."

Police don't have time to sit with people for hours. "But we can," Smith said, "so they call us."

Firefighters, too, are spending more time with the people they serve, through an overdose detail organized last fall. The members, who are EMTs, had noticed how much time they were spending racing to scenes in ambulances and fire engines. They suggested dedicating a smaller crew to the task, and within a month, the Community Response Team was born. The two-person squad zips around in a pickup truck stocked with drug test strips, doses of Narcan and supplies to treat the persistent wounds caused by the animal tranquilizer xylazine, a common additive to illicit drugs. Run as an overtime shift, the team averages 50 hours on duty each week.

Without the pressure of getting a fully staffed ambulance to the hospital and back in service quickly, team members often have time to get to know the people they treat, who tend to be open to conversation after being revived. Firefighters say it's making a difference, both for patients and squad members who, faced with treating people again and again for overdosing, are battling compassion fatigue.

"The difference is that personal connection," said Josh Kirtlink, president of the Burlington Firefighters' Association and an occasional response team member. Hearing people's stories "changes your outlook on what you can do to help them," he said.

The department is leveraging that sentiment to launch another effort, which would provide patients with immediate addiction treatment. Called PREVENT, the state protocol allows paramedics to offer buprenorphine to people in withdrawal after treating them for overdosing; Burlington has asked the state to allow its emergency medical technicians to do so, too. Bupe, a drug that curbs opioid cravings, is only available to people with a prescription.

The state is still reviewing Burlington's request, but Fire Chief Mike LaChance said it would help people who refuse to go to the hospital after overdosing — which happens about a third of the time.

"[Bupe] brings them back toward normal," he said. "Maybe they will be in a mental space to say, 'OK, yes, I will accept some help.'"

Burlington's ever-growing menu of services can be difficult to navigate — so much so that the city recently created a "Downtown Safety and Security Guide," a flowchart-like handout that advises workers on whom to contact in the event of various emergencies.

The services aren't always available. None of the police department's unarmed workers is on duty 24 hours a day, though they do work every day of the week. The fire department's overdose team only runs when EMTs sign up for shifts, and it's been harder to fill them during the summer vacation season.

The city has also struggled with hiring. The police department is budgeted to have 10 community service officers, but only five are on the payroll — partly because some have been hired and then gone on to become full-fledged Burlington cops. The department has been trying to create a mental health response team for months but hasn't found enough clinicians to launch it.

Despite the efforts, some people aren't ready to accept the help.

Back on Church Street, the man revived by EMTs threw up on the brick walkway as people strolled by with shopping bags and ice cream cones. A stretcher waited to whisk him to the hospital. When he declined to go, EMTs gave him a pouch with more Narcan and headed back to the station.

The man took a jug of water offered by employees from the nearby Urban Outfitters store. Then he got up and walked down the street, leaving the bag of supplies on the bench.

Taking Care of Businesses

Homeport had only been open for a few hours one July afternoon when a man beelined for the back of the store, stuffed items into a backpack and left. The store's security guard, Connor, grabbed his cellphone and furiously texted a message, attaching a clip of surveillance footage.

"The guy with the green backpack just stole from us," wrote Connor, who didn't want his last name published due to security concerns. "We're looking for them now."

His phone buzzed: Someone had spotted the man near the Fletcher Free Library. Within minutes, Connor and another person who works downtown bounded down Church Street in pursuit.

They caught up to the man, who eventually surrendered the goods. Later that day, two canvas shoulder bags — priced at $30 apiece — were back on the shelf.

Driven by desperation, addiction or both, thieves have become bolder and more aggressive. Merchants, no longer able to rely on police for help, have had to get creative. Workers exchange information on a WhatsApp group chat about suspicious behavior. Some have hired private security, while jewelry dealer Von Bargen's keeps its doors locked during business hours, admitting customers only after they ring a doorbell.

The Burlington Business Association, meanwhile, has hired someone to help workers who run into trouble with patrons. The org has also teamed up with the University of Vermont Medical Center to train employees on how to lower the temperature when dealing with rowdy or intoxicated people.

"We could potentially be close to a tipping point if, in fact, we don't address this," said Patricia Pomerleau, whose prominent family owns plenty of downtown real estate. The Pomerleau Family Foundation is helping pay for one of the programs. "Let's make sure that doesn't happen."

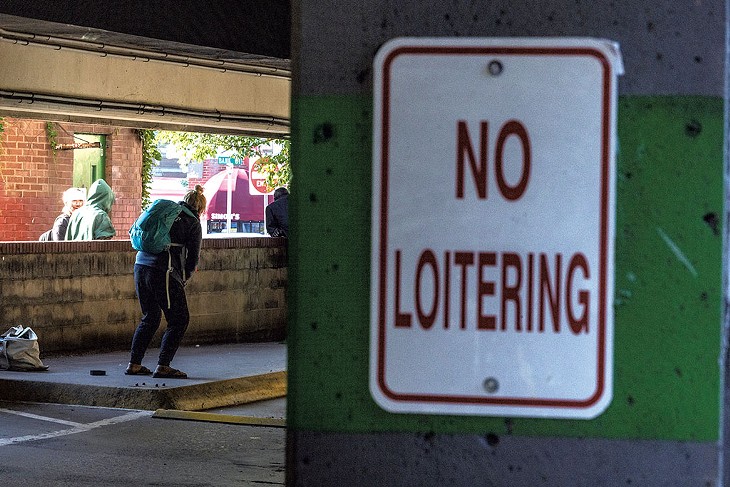

Business owners have long been vocal about the state of downtown. They've lobbied legislators for stronger anti-loitering laws and city councilors for private security on Church Street. A handful have relocated or downsized their stores in recent years, some because of theft and a perception that downtown is unsafe. Earlier this year, an international brand backed out of a lease deal for a Church Street space due to safety concerns.

Data, though, show that people are still drawn to the Queen City. Two million people visited Church Street in 2023, on par with pre-pandemic numbers, cellphone data show. That same year, shoppers spent 2.4 percent more in retail stores than they did in 2019, before the pandemic hit, according to city tax data. Hotels, meantime, showed an 8.3 percent increase, though restaurant receipts dipped 10.3 percent.

click to enlarge

- James Buck

- Marsha McCombie (left) and Lacey Smith (center) meeting with Debbie on Main Street

Most of the empty storefronts on the Marketplace are filled now or have tenants lined up. Businesspeople who had been heralding Burlington's demise are now publicly projecting optimism, perhaps realizing that their previous messaging could actually be to their detriment.

"I just decided a few months ago that I didn't know how helpful it was to continue to be raising the red flag," said Kelly Devine, who, as executive director of the Burlington Business Association, has been one of the most outspoken about the state of downtown. "[I'm focusing] less on the problem, more on solutions."

The WhatsApp group is one such strategy. Merchants use the app to share photos and descriptions of suspects. Other times, workers will ask someone to come stand in their shop to let would-be thieves know they're being watched. In other cases, they've chased down criminals who stole stuff. The group operates much like BTV Stolen Bike Report and Recovery, a Facebook page whose 4,400 members have tracked down hundreds of boosted bikes since it formed in 2022.

Ryan Nick, a property manager for Nick & Morrissey Development, helps moderate the private chat for downtown businesses.

"If no one else is coming, it's up to us to fend for ourselves," he said. "We're all trying to support the street and trying to make the street a safe and fun place to be."

Things can get hairy. In June, someone posted on WhatsApp that a woman was stealing from lululemon, a high-end yoga clothing retailer that rents from Nick and is a popular target for thieves. Nick and his father, Nick & Morrissey Development partner Jeff Nick, responded and confronted the woman. The ensuing scene was caught on camera: Jeff latched on to the bag of goods while a bystander gripped the woman's arm. She pushed and pulled until she broke free, losing a sneaker but getting away with the bag. Police were too busy to respond.

A new pilot program may bring some relief. Using the same WhatsApp group, workers can summon a "downtown ambassador" for help. Stationed in a closet-size office next to the Church Street CVS, Andrew LeStourgeon is the face of the program, which will run at least through September. The former owner of the now-closed Monarch & the Milkweed café is on call to help workers file police reports and to escort them to their cars at night.

He also gets to know people with substance-use disorder and, if they're willing, refers them to the "Downtown Health Project," a collaboration between two agencies focused on harm reduction: the low-barrier Johnson Health Center on Bank Street and Vermonters for Criminal Justice Reform, a nonprofit that helps people find housing and get drug treatment. The Pomerleaus recently donated $300,000 to the organizations to support their work.

"My goal is to be a supportive presence downtown and to connect people with the help they need," LeStourgeon wrote in an email. "I have never loved Burlington more than in the last three months of doing this important work on the streets."

Devine acknowledged that LeStourgeon's two roles could be at odds, when he's asked to build trust with the very people he could be helping report to the police. His background in hospitality will help, Devine said. And LeStourgeon won't forcibly take stolen goods from shoplifters' hands, according to Devine.

So far, merchants are reporting that his presence has deterred theft, including at lululemon, Devine said.

"This is definitely experimental at this point," she said. "I'm happy to try things out and see if they stick."

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

Moral Quandary

Lisa and Kim had an hour to pack up and leave.

The two women had spread a down comforter under a tree at First Congregational Church, where, 20 feet away, a sign warned that camping isn't allowed. That hadn't stopped Lisa, Kim or a half dozen other people from sleeping outside the sprawling brick building on South Winooski Avenue that July morning.

At 11 a.m., church staffer Ava Bilton was about to rouse the women for the last time when two men approached her. Lisa had just overdosed, they said.

Outside, Lisa was on all fours, retching on Kim's white blanket. EMTs helped her up and took her to the hospital. Bilton surveyed the scene, which had attracted a small crowd, and spotted a man digging a baggie of white powder from his pocket.

"You can't do drugs here, Mike," Bilton warned. "We just had an overdose."

"I don't do nothin'," he said.

"I just saw the needle out!" Bilton said, exasperated. "Is that for your diabetes?"

Bilton began cleaning up the campsite. Once she looked away, Mike prepared a syringe, found a vein in his hand and pressed the plunger.

This was a typical morning at First Congregational, which has long dealt with illegal camping and drug use. But the activity has become harder to manage, and now, other houses of worship are seeing the same. As a result, local clergy are wrestling with how to balance compassion and security. Sometimes, that means asking people to leave; others, it's offering them food and inviting them in to talk.

"We're trying to figure out what our call is in this moment," Pastor Ken White of the College Street Congregational Church said. "It's gotta be more than, 'Get off our lawn.'"

White can pinpoint when things got worse. One June morning, the city strung tape across a bus shelter next to the Fletcher Free Library, preparing to remove it after complaints about people sleeping, fighting and using drugs there. That afternoon, the crowd moved a few hundred feet up College Street — to White's church.

The pastor had hoped to allow people to hang out, but not sleep, on church property, as long as they were respectful. But after a woman screamed at him, drug dealers set up shop in the parking lot and police responded there, all in a span of hours, White realized the situation was too much for him to manage. Anyone loitering is asked to leave.

"Kicking people out who are down is soul killing," White said. "We're having to turn the church into something we never wanted to be: ... a no-public zone."

White realizes, of course, that if people aren't on his lawn, they're on someone else's. Lately, it's the grass at the First Congregational and First United Methodist churches.

The buildings are on either side of Buell Street, which has become a hot spot in its own right. In late July, Burlington police arrested a 37-year-old Hartford, Conn., man for dealing drugs there, but the trade has continued unabated. The morning of Lisa's overdose — just days after the drug bust — three people were passed out in a black BMW, including the driver. A person was unconscious in a tent on the greenbelt. A man rolled up on a bicycle and asked an unhoused man and a Seven Days reporter if they were looking to buy some Percocet.

At First Congregational, staff spend much of their workday policing such behavior, as well as counseling people and giving them wound care kits. After hearing about violent incidents that occurred once employees had left for the day, Rev. Elissa Johnk was weighing whether to hire overnight security. "A lot of people have nowhere to go," she said. "It's this really hard call. We have to keep the space safe."

Misbehavior is increasingly problematic at the Methodist church next door. Two years ago, a man pulled a knife on the church's pastor, Kerry Cameron, and earlier this year, threatened to kill her entire congregation. Last fall, someone took a sledgehammer to the church's front steps, causing $30,000 in damage. In June, the building's copper downspouts, worth $7,000, went missing. Cameron recently put up no-trespassing signs around the property.

Word is getting around. One recent afternoon, an unhoused woman who goes by Tammy confronted Cameron about the trespass rule, saying all unhoused people were being punished for the actions of a few. "People are angry because they don't know what to do," Tammy said.

Cameron feels similarly flummoxed. Churches are called to perform acts of kindness, she said, noting that hers hosts 30 12-step programs and a thrift shop. She's baptized homeless people and even threw a wedding for an unhoused couple. But a beleaguered church can't help anyone, she said.

To remind herself of that, Cameron printed out a stack of yellow note cards and put them on her office coffee table. "You can still be a kind person if you set boundaries, if you protect your time and space," they read. "If you say no."

Scripture guides her thinking, including Ephesians 6:11, a verse that speaks of drawing on God's strength to stand against evil. "I am boldly saying the drug is the devil," Cameron said. "In my world, it absolutely is."

The clergy have been in touch with the city, which has sent more police officers and social workers to patrol the block. And some church members have started programs that they hope will enable them to forge better relationships with the unhoused people congregating on their grounds.

Sunday Morning Breakfast, at the First Unitarian Universalist Society of Burlington, invites people for peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, juice, and coffee every week, even on holidays. About 35 people came to the first breakfast last fall, but attendance has swelled to more than 100 in recent weeks.

The Methodist church started a similar event, the Share, around the same time. Instead of just grabbing a meal, guests are asked to stay and tell their stories.

On a recent Sunday evening, volunteers scooped homemade egg salad onto slices of wheat bread and poured steaming-hot vats of kielbasa and chicken noodle soups into slow cookers. Just before opening the doors, the kitchen crew clasped hands and prayed that their guests would leave full and satisfied.

People trickled in from the church lawn, grabbing packets of mayo and mustard for their ham sandwiches. A woman let her pet bunny, Benjamin, roam as she tucked into her meal. A tattooed man with a pierced septum thanked Pastor Cameron for the food.

At another table was James, scruffy and soft-spoken in a T-shirt streaked with dried paint. Declining to share his last name, James said he's in recovery and attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in the church basement. He said it's difficult to walk past people using drugs on the lawn when he's trying to stay clean.

"You can't have money in your pocket and a weak moment," he said. "You may not make it in the doors."

That night, however, James was focused. He finished his soup and went to change, not wanting to show up at an AA meeting in a dirty shirt.

The Long View

With no obvious solutions to Burlington's problems, those charged with addressing them are tossing around ideas. Some could quickly show results while others will require more time — a hard truth when the status quo feels untenable.

At city hall, Mulvaney-Stanak has conferred with a panel of advisers to discuss safety issues. The group, including business leaders, housing experts and attorneys, met four times over the past three months. Mulvaney-Stanak outlined some of their recommendations at Monday's city council meeting.

The mayor first plans to address hot spots for crime and misbehavior, work that started with closing the library bus shelter. Besides church lawns, the activity has migrated to a city-owned parking garage on Cherry Street, where officials are considering hiring sheriffs to patrol. The extra security could allow the city to reopen two stairwells it closed in June to counter rampant drug use.

Buell Street is also on the list. Police and social workers have upped their patrols of the area, the mayor said, and the city has been in close contact with church leaders.

Those efforts don't seem to be working, some city councilors said on Monday, noting that people are arrested and released only to reoffend. They suggested hourly police patrols of the neighborhood and that the mayor pressure county prosecutors to crack down on criminal behavior.

"Although these problems are difficult, there are some aspects that are not," Councilor Tim Doherty (D-East District), a former federal prosecutor, said. "It shouldn't be that difficult to prevent people from, at 11 o'clock on a Tuesday morning, just parking in the middle of Buell Street and dealing bundles of fentanyl out the window."

Councilor Melo Grant (P-Central District), meantime, said she appreciates the mayor's approach — and recognizes it will take time to work.

"We didn't get here overnight, so we're not going to get out of it overnight," she said, "but for the first time, I have hope."

Mulvaney-Stanak also announced on Monday that retired Vermont State Police commander Ingrid Jonas will serve as her senior community safety adviser, a temporary position she had proposed during the campaign. Jonas is charged with streamlining the city's response to homelessness and crime, work that's currently spread out among several city departments.

It will take time to hire more police, another part of the mayor's plan. The city's current budget would pay for up to 75 officers, but recent hiring trends suggest that the city won't have that many officers anytime soon; currently, 66 are on the payroll.

At a recent meeting of the council's Public Safety Committee, recruitment officer Cpl. Carolynne Erwin said 26 people applied for police jobs this year, compared to 112 in 2023. Eleven advanced in the hiring process, but only three made it through a physical, polygraph test, interview and background check. "This trajectory is insanely low," Erwin said.

The most buzz this year has been around opening the state's first-ever overdose-prevention center. In June, the Vermont legislature freed up $1.1 million to create a center in Burlington, where people could use drugs under supervision. City officials hope that would reduce outdoor drug use and help, eventually, to get people into treatment.

But questions remain, chiefly who will operate it and where it will go. Mulvaney-Stanak says the center shouldn't be located near schools or addiction recovery services. She also suggested that her neighborhood of the Old North End already has its fair share of services and shouldn't have to host more.

The city will have a "robust community engagement process" about the location, Mulvaney-Stanak said. Meantime, officials are looking into zoning hurdles and consulting a heat map of overdose calls to see where people are already using.

Mulvaney-Stanak hopes the center could be open within a year. But "this needs to be done well," she said. "Many eyes are on us."

Some residents want more urgency. Rachel Furnari, who lives on Orchard Terrace, has been emailing city officials, Gov. Phil Scott and Vermont's congressional delegation about the situation on nearby Buell Street, saying she can no longer walk there with her small children. The mayor's office responded with what seemed to Furnari like a policy memo that lacked any new information.

"Everyone you call says there are no immediate solutions," she said. "No one's even throwing out creative ideas or providing any hope to us in our little neighborhood. No one. I think that's the part that has me really down right now."

Some new initiatives are on the way, however.

click to enlarge

- Courtney Lamdin

- Howard Center's Cathie Buscaglia at the future mental health urgent care center in Burlington

A light-filled office on South Prospect Street is currently being renovated to become the county's first-ever urgent care center for people in mental health crisis. Operated by Howard Center, the clinic will offer mental health assessments and medical care for walk-in patients, mostly at no cost. It's funded for the next three years.

A hard-hat tour of the space earlier this month showcased views of Lake Champlain and ample treatment rooms that will be painted calming shades of blue. Eschewing the sterile feel of a traditional doctor's office, the waiting room will mimic a modern living space with white furniture and a recessed television.

The center will relieve pressure on the University of Vermont Medical Center emergency room, a common but inadequate landing spot for people in crisis. But it will only be open weekdays and is a bit of a walk from downtown.

Regardless, "this is going to fill that gap in a way we just haven't had," said Stephen Leffler, president of the hospital, one of several organizations involved in the project. "I'm really excited for the service this is going to be for our patients."

Housing is also part of the puzzle, including units for people transitioning from homelessness. Nine such apartments will be available in a 38-unit complex that affordable housing developer Champlain Housing Trust is building on South Winooski Avenue. More than half of the 51 apartments built by the housing trust in the past year were leased to formerly unhoused people, data show.

Still, it will be more than a year before the Burlington units are ready for move-in, housing trust CEO Michael Monte said. In the meantime, the nonprofit is in talks with the city about opening another homeless shelter, at the former Social Security office on Pearl Street.

"We're really going to need a few years in order to move out of this situation we're in right now," Monte said.

That's precisely what Furnari, the Orchard Terrace resident, fears most.

She has always seen drug use in the neighborhood and people congregating at the aptly nicknamed "Beer Tree," a handsome linden on Buell Street that provides shelter to revelers after dark. But the misbehavior and lack of a real plan to address it worries her. The day she emailed local and state officials, she'd watched as people injected drugs into each other's necks. It was miserable to witness, Furnari said, and likely worse for the people involved.

"The community has changed," she said.

And yet, she's adapted to it. On a recent Friday afternoon, during a phone interview with a Seven Days reporter, Furnari was taking in the sights of the annual Festival of Fools on Church Street, where crowds had gathered to watch street performers entertain. She paid little mind to the sirens that got louder and louder in the background.

The emergency responders, it turned out, were headed straight for her neighborhood.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Downtown Dilemma | Plagued by homelessness, drugs and safety concerns, Burlington tries to adapt to a new normal"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Courtney Lamdin

Bio:

Courtney Lamdin is a news reporter at Seven Days; she covers Burlington. She was previously executive editor of the Milton Independent, Colchester Sun and Essex Reporter.

Courtney Lamdin is a news reporter at Seven Days; she covers Burlington. She was previously executive editor of the Milton Independent, Colchester Sun and Essex Reporter.

More By This Author

Latest in City

Speaking of...

-

Readers Weigh In on 'Bad News Burlington'

Sep 4, 2024 -

Dining on a Dime: Quick Nepali Eats at Burlington's CK Dumpling House

Sep 3, 2024 -

New Spots to Eat at Burlington's South End Art Hop

Sep 3, 2024 -

From the Publisher: Bad News Burlington

Aug 28, 2024 -

Amid a Volatile Industry, Burlington May Lose Its Only Cinema

Aug 21, 2024 - More »

find, follow, fan us: