Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

Marshfield's Jules Rabin Celebrates a Century of Intellectual Curiosity, Trailblazing Bread and Peace Activism

The spirited centenarian has made his mark in the Goddard College classroom, through his Upland Bakers bread business and at decades of peace vigils.

Published August 7, 2024 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated August 13, 2024 at 9:46 p.m.

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Jules Rabin

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

Jules Rabin describes the current state of Montpelier's Friday peace vigil as "kind of schleppy," a Yiddish word for awkward or undistinguished. Despite his characteristically forthright assessment, Rabin has been a steadfast attendee for the better part of two decades. Most weeks, the 100-year-old drives himself from his home in Marshfield to join a handful of senior citizens in front of the old post office, wielding well-worn signs proclaiming, "War is not the answer," "Climate Action Now" and "Free Gaza."

On June 7, Rabin joined five fellow protesters on State Street. He had navigated his red Toyota RAV4 to the Capital City through a brief, intense rainstorm. "I hardly noticed it," he said. Barely five foot three, the elfin Rabin wore a collared turquoise shirt, khakis and a jaunty straw boater suited for a picnic lunch.

But his sign made clear this was no picnic. Neatly handwritten in red capital letters, it read: "Killing & starving: what Nazis did to Jews 80 years ago, my fellow Jews in Israel do to Palestinians today. I don't hear God crying."

Born Yehuda Moishe Rabinovitz on April 6, 1924, Rabin was the youngest of five children of uneducated Eastern European Jewish immigrants who lived hand to mouth in Roxbury, Mass. Rabin is not religious — he calls himself a Jewish atheist — but he identifies strongly as Jewish. "As a tribe, we Eastern European Jews have our customs and deep attitudes," he explained. "'See something, say something' is part of my Jewish culture."

As such, he said, he feels compelled to speak out against injustice wherever he sees it, from the Vietnam and Iraq wars to the situation in Gaza, which he has been protesting for years. Though Rabin is not temperamentally suited to be a movement organizer — "He can't stand meetings," said his wife, Helen — his deep commitment and talents as an articulate and tireless spokesperson distinguish him.

For more than half a century, Jules has been a dedicated presence at marches and vigils and in letter-writing campaigns. "He will always show up," said Joseph Gainza, a fellow activist and friend of three decades.

That's still true, even at 100. After 30 minutes of standing under the bright sun with his sign, chatting with fellow protesters and a few passersby, Jules headed back to his car. In a concession to age, he now stays for only half of the hourlong vigil.

click to enlarge

- File: Terry Allen

- Jules Rabin at his 100th birthday protest in Montpelier with supporters including his grandchildren Eva and Lucien Theriault (center) and friend Peter Schumann (right)

A couple scurried over as he prepared to drive away. Chandra and Roger Cranse told Jules they had been devotees of Upland Bakers, the naturally leavened, wood-fired bread bakery with which the Rabins supported their family of four in the days before such bread was familiar to many Americans.

"Your bread is still my favorite," Roger said to Jules. "It was the first of its kind of artisan bread in Vermont," he added, in case a nearby reporter was unaware.

During its initial 24-year run, from the late 1970s to the early 2000s, Upland Bakers gained a national reputation and a passionate following, despite the fact that the Rabins never made more than 300 loaves a week. "They truly are legends in the baking world," said Blair Marvin, co-owner of the small, highly regarded wood-fired bakery Elmore Mountain Bread.

In 1968, the Rabins moved from New York City's Greenwich Village to Vermont for Jules to teach anthropology at Goddard College. They arrived in the heyday of the experimental liberal arts institution in Plainfield, and the couple immediately felt at home with the leftist, antiestablishment ethos. The Rabins labored with local carpenters to build the home in Marshfield in which they still live, tended a large garden and sank deep roots into the creative, intellectual, back-to-the-land community that mushroomed symbiotically around the college. Jules helped add a jewel to Vermont's counterculture crown by coordinating the effort to bring Bread and Puppet Theater to Goddard for a long-term residency before the renowned troupe settled in Glover in the early 1970s.

Just as Goddard has had an enduring impact on Vermont's culture, the spirited centenarian has made his mark on those he inspired in the classroom, through the bakery and on the streets. On April 9, the 86-year-old college announced its permanent closure after several decades of financial challenges. Jules, on the other hand, is still going. Just a few days before, he commemorated his 100th birthday with a special Saturday protest.

About 75 family members, friends and acquaintances gathered at the corner of Montpelier's State and Main streets. Sen. Andrew Perchlik (D/P-Washington) presented him with a copy of a Vermont General Assembly resolution congratulating him on his many accomplishments. Jules' youngest daughter, Nessa, read aloud the fourth letter her father had sent since October to the Israeli ambassador to the United States, pleading for an end to what he described as "the bloody craziness being wrought in Gaza." Others came bearing political signs, flowers, cards and a majestic seven-pound loaf of bread to honor the former professor and baker, who continues, literally, to stand up for what he believes in.

"I'll do it as long as my legs hold up," Jules said. At his birthday protest, he did himself one better: He dropped to the sidewalk, in his full-length wool coat, and did 10 push-ups.

A Life of Intellectual Curiosity

Jules again did his push-up routine, minus the wool coat, at Bread and Puppet cofounder Peter Schumann's 90th birthday celebration in early June. "What a show-off!" Schumann joked, delighted that his old friend is still up for lighthearted displays of prowess.

When Jules started volunteering with Bread and Puppet in New York City, in the early 1960s, Schumann was thrilled to find someone with whom he could chew over the theories of German thinkers such as Ernst Bloch and Bertolt Brecht. The men still revel in their deep discussions, enriched by their broad knowledge of literature, philosophy and politics. "Jules is one of the best conversationalists I can think of," Schumann said.

Such intellectual exchange was not part of Jules' early life. His mother, an immigrant from Lithuania, was illiterate, like many women of her background. She lived until 101 without learning to read, to her son's disappointment. His father read just enough Hebrew to have a bar mitzvah and just enough Yiddish to understand the newspaper.

Jules described his parents as "urban peasants," scratching out a living in Boston with little time or energy for other pursuits. But his uncle, a fervent Marxist, encouraged the development of his political conscience: Jules was 8 when his uncle took him to his first protest for the Black labor organizer Angelo Herndon, who had been convicted of insurrection.

Jules' father, Pinchas (anglicized to Philip) Rabinovitz, mostly worked sorting scrap metal, with a sideline bootlegging during Prohibition. He sometimes took his youngest along as a decoy on liquor delivery runs. "He would ask me in a very humble way if I would go with him. He didn't speak with authority," Jules recalled.

During the Depression, the family managed to buy a small variety store in Roxbury and lived in a series of shabby apartments whose addresses Jules can still rattle off. From 7:30 a.m. until 10 p.m., the five children took turns tending the store, since their parents did not speak English.

Jules remembers spending long summer days waiting for infrequent customers to buy cigarettes, penny candy, newspapers, milk, bread and "cold cuts threatening to go moldy." He and his siblings could have snuck candy to compensate themselves, but they never did. "We pitied our parents," Jules said.

Along with his childhood addresses, Jules recalls the exact number of the library card he got when he was 6. "I think brains are equally given to all of us. I think it's the kind of life you cultivate," he said. "I somehow had a thirst for reading as a kid, and so I cultivated a life of literacy and literature." Although his family was not religious, Jules said his love of reading was partly inspired by the historic devotion of Jewish men to "endlessly reading and trying to pull meaning" from religious texts.

He insists he was not an exceptional student, merely a "dutiful" one. His primary school teachers apparently thought otherwise. At their encouragement, he applied to the prestigious Boston Latin School, which he attended for six years.

Either due to hubris or naïveté — Jules isn't sure which — he applied only to Harvard University during his senior year at Boston Latin. Luckily, he got in. After graduating in 1941, he worked for a year as a dishwasher and stock boy to earn the $400 for his first semester's tuition, a sum his parents could not spare. College was interrupted by two years of military service, which Jules did willingly, despite his pacifist leanings. "I was struck by the terror and absolute cruelty of the Nazis," he said. He trained as a German translator but was not deployed overseas.

Between the army and his return to college, Jules changed his surname. The multisyllabic Rabinovitz was "awkward" during military roll call, he explained, and he wanted to simplify it, not an uncommon choice among first-generation Jewish Americans. His older brother became Robbins, and one of his sisters chose Ray, but "I wanted to hold on to those two syllables that were Jewish," Jules said. Antisemitism had quietly haunted his Boston childhood. Kids would ask if you were Jewish, he recalled, "and you'd get a smack if you were." He lived in constant fear of being beaten up.

At Harvard, Jules struggled to fit in. "On the whole, I was lonely," he admitted. His upbringing had not equipped him to move with ease among his fellow students, many of whom came from upper-class privilege. But he did blossom intellectually. His interest in Marxism, instilled in him by his uncle, led him to study sociology and anthropology. "I wanted to get to the depths of the social machinery," he said.

Jules graduated from Harvard in 1948, although he did not complete his senior thesis. This commenced a pattern of failing to complete major writing endeavors. He never finished his Columbia University doctoral dissertation on the shortcomings of the scientific method in anthropological research, nor a book about the role of bread in the lives of late 18th-century English farm laborers, of which he wrote 350 pages.

"I chicken out of things," Jules said. Then he corrected himself. "I don't like the term. It's not part of my vocabulary. I withdrew because I don't press myself too hard. I know when to withdraw." He insisted that he is not afraid of failure. "I'm confident in what I write," Jules said. "I do what I can do without tying myself into a knot."

The couple's eldest daughter, Hannah, theorized that her father does the work up to the point where he is "intellectually satisfied." She said he likes to do things "90 percent," which he judges to be enough. "That's his theory about washing dishes, too," Hannah added with a laugh.

That said, his family and former students describe Jules as 100 percent committed to cultivating his intellect and theirs. He esteems intellectual curiosity and respects those with a drive to learn. When he encountered Helen, who is 17 years his junior, he said he was drawn to her "very competent mind."

The couple met at an organizing meeting for the General Strike for Peace in late 1961. Helen was a Barnard College student taking time off to work at the Greenwich Village Peace Center and save up tuition money. Jules had recently returned from a monthslong international walk for peace from the United States to Moscow, organized by the antinuclear Committee for Non-Violent Action. He had signed on as a cameraman with a documentary crew filming the endeavor but ended up becoming a full-fledged participant. Since he had arrived in New York City for graduate school in 1951, Jules had been part of the heady stew of arts and activism bubbling in Greenwich Village, but the peace walk galvanized him, he said.

In comparison with men her age, Helen said she found the 38-year-old Jules empathetic and interesting. The couple picnicked on clams on the half shell in Washington Square Park and attended avant-garde dance shows. They participated in vigils against the Vietnam War and demonstrations for civil rights. At the 1964 New York World's Fair, they were among those arrested during a sit-in at the beer pavilion to protest racist hiring practices.

Although they were not legally married until 1981, Helen took Rabin as her last name, and the couple had their first daughter, Hannah, in 1966. Jules, whose PhD experience had soured him somewhat on academia, worked as a truck driver. The family was living in a Greenwich Village tenement with a bathtub in the kitchen when an acquaintance mentioned that a small Vermont college was looking for an anthropology professor. Applying for the job seemed the responsible thing to do, Jules recalled.

Goddard didn't care that he hadn't completed his dissertation. During Jules' nine years as a professor, the college's faculty included some of the country's leading radicals and progressive thinkers, including anti-capitalist ecologist Murray Bookchin, cofounder of the Marshfield-based Institute for Social Ecology; and John Froines and David Dellinger, two members of the so-called Chicago Seven who were prosecuted for anti-war protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Musician Paul Boffa couldn't remember the exact course he took with Jules in the mid-1970s, but he recalled his professor as warm, encouraging and inspiring. "He could have taught cookie baking, and it would have been equally engaging," Boffa said.

"He was someone who really seemed to embody and live out his beliefs," said Dan Chodorkoff, a Goddard student who later cofounded the Institute for Social Ecology. Jules drove a BMW motorcycle to campus and "cut quite a figure," Chodorkoff added.

The family easily transitioned to the Greenwich Village version of country life. The Rabins' daughters remember constant, energetic debate at gatherings over meals and during movie nights, when their father would project films about anthropological subjects, such as the Netsilik Inuit of northern Canada, on an old-fashioned, roll-down screen. When Hannah became disenchanted with school in seventh grade, her father proposed they do an independent study together and assigned her readings from texts he taught at Goddard.

Jules has continued to provide the same kind of intellectual support for his grandchildren. Hannah's children, Eva and Lucien Theriault, and Nessa's son, Julian Soberano, shared vivid memories of being encouraged by their grandfather to look up words in the tissue-thin pages of the enormous Webster's dictionary on a stand near the woodstove.

Eva, now 30, said her grandfather still sends her emails dedicated to the explication of a single word. Recently, it was "indefatigable."

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

By Bread Alone

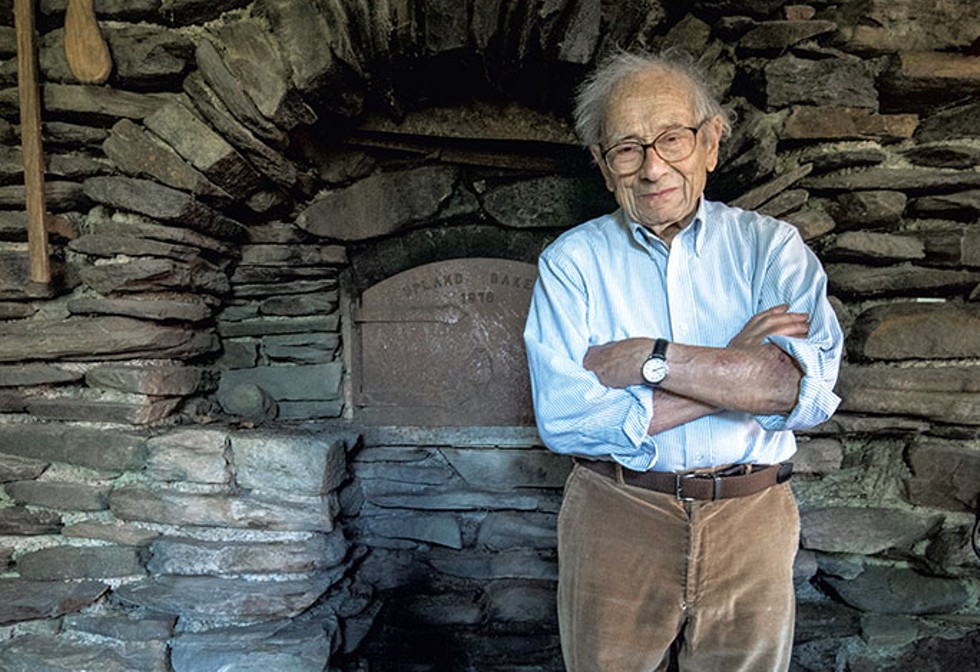

click to enlarge

- File: Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Jules and Helen Rabin teaching at Barre's Rise Up Bakery in 2019

In 1971, the Rabin family took a sabbatical in France, which included a week near Montpellier in what Jules described as "a very serious, intentional community, where bread was central." About 100 people lived an 18th-century life, weaving their own wool for clothing and subsisting largely on huge round loaves called miches.

The loaves were baked in a communal oven, as was historically traditional throughout Europe, and the community viewed them as the sacred source of life. "They didn't speak of bread as holy, but they treated it as a holy object," Jules said.

Bread had also been venerated during his youth. "My father always ate with a piece of good rye bread in one hand," Jules recalled, and often repeated a Yiddish proverb that translates to: "Eat bread and you will fare healthfully."

Jules and Helen returned to Marshfield inspired to build a stone oven similar to those they had seen in France. They gathered fieldstone from neighboring fields, and Helen led the design and construction of an impressive 15-foot-high brick-and-stone oven, with little in the way of how-to guides. "I'm most proud of Helen's building that oven," Jules said. "It was she who laid every brick and every stone."

In 1970s America, "There were just a few voices crying in the wilderness about good bread," reads the profile of Upland Bakers in The Bread Builders: Hearth Loaves and Masonry Ovens. The 1999 book, by Daniel Wing and Alan Scott, became a bible for serious bakers. According to Jeffrey Hamelman, original director of King Arthur Baking's Norwich bakery, who started his baking career around that time, "America was still in kind of Wonder Bread mode."

When they built the oven, the Rabins never envisioned making a living selling bread. But after Jules was laid off from Goddard in a round of faculty cuts in 1977, the couple sat down at their dining room table to brainstorm how to stay in Marshfield.

The job loss prompted Jules to reconsider his career path. He noted that many in the '60s rejected cerebral pursuits for manual work, as he did when he became a truck driver in the city. "Baking bread — what could be more worthy?" the Rabins recalled thinking. "It's earnest. It's honest. It's basic."

The couple set about establishing a business that could provide just what they needed to live simply and stay true to their ideals. "It was family-tailored," Jules said of their resolve to stay small. "And somewhat anti-capitalist," he added.

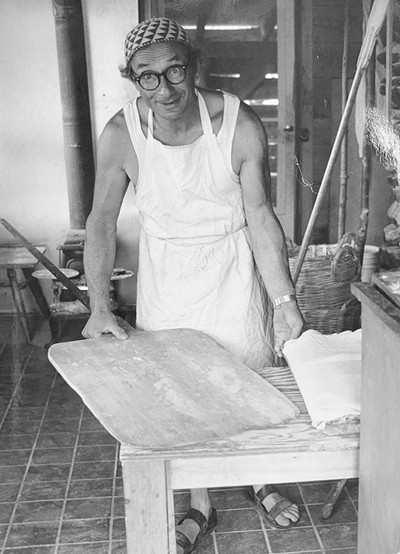

They baked four days a week for 13 years, driving their loaves to fewer than a dozen stores and markets only as far north as Hardwick and as far south as Montpelier. After Nessa's college graduation, they cut back to three days a week until their initial retirement in 2002, when Jules was a couple of years shy of 80.

Their daughters have deep sensory memories of the rhythms of the bakery —the smell of the early-morning woodsmoke when their father started the fire, then coming home off the school bus into the cozy bakery, where public radio would be playing as their mother and father worked together to pull fresh bread from the oven. They fondly remember the mini-loaves their parents made for them as an afterschool snack, sometimes studded with chocolate.

Upland Bakers' four-pound miche, Jewish rye made with freshly ground rye flour, light wheat loaf and French-style bâtard achieved something approaching cult status. Nessa occasionally tagged along on deliveries with Papa, as his daughters still call him. "I remember thinking, Oh, my God, my father's a celebrity — like, People are waiting for this bread," she said. She also recalled her father's exhaustion when he sat down for dinner after a long, physically demanding day, "smelling like bread and warmth."

The Rabins made bread just like they had eaten in France, using only natural sourdough leavening and wood heat. "We were so devoted to the craft," Jules said. "We were patriots of the idea of artisanal baking."

For many in Vermont, Upland Bakers set a gold standard. "The greatest honor is still sometimes when people say, 'This bread is almost as good as the Rabins' bread,'" said Randy George, co-owner of Red Hen Baking in Middlesex.

The couple shared equally in the daily baking routine and never hired help. They had a clear division of labor: Helen worked in the morning on the dough, then the couple shaped bread together through the afternoon. Jules built the fire, starting at 5:30 a.m., and finished the baking in the late afternoon or early evening. Jules may have been the public face of the bread, but "Helen was the genius of the composition of our bread," he said. "She had to have a feel for the dough as it developed."

As in their activism, Jules has always been the more visible of the pair. "My mother is a quiet force. My father's the PR guy," Hannah said. Helen never minded that people often called it "Jules' bread," she said. "He was always careful to say that it was my bread, too."

Hamelman, who later started the bakery at King Arthur, first tasted Upland Bakers' bread at an antinuclear march in Brattleboro — one of the many strikes, protests and marches where the Rabins donated loaves in support of activists. "I remember that slice of bread 45 years later. It sang to me," he said. "It was agreeably sour. It was agreeably dense. The crust was robust. It wasn't a timid bake. There was character to it. It was just profoundly well-made bread."

A 1987 New York Times article declared, "Americans are ready for better bread." It described Upland Bakers' "marvelously crusty sourdough breads" and praised its approach as an exemplar of "the most traditional method."

Around the same time, Hamelman finally met the Rabins. He later asked if he could come bake with them, and they welcomed him at their house for a week. "They had such a choreography between them that they probably could have gone through a whole bake cycle without even talking," Hamelman recalled. "It was like a ballet."

Eight years after they retired, the Rabins fired up the oven again, in 2010, prompted by their grandson Julian's interest and his need for a summer job. They sold bread for a few seasons just at the Plainfield Farmers Market. Their neighbors welcomed them back with an enthusiasm equivalent to die-hard Phish fans at a comeback tour.

"It was a celebration," Jules said.

"It was good bread, besides," Helen added.

Hamelman observed that both the bread style and the scale of Upland Bakers hewed to tradition. "They did what bakers have done for millennia, which is bake for your community," he said. "They never aspired to be a boulder in the pond."

'Small Pleasures'

click to enlarge

- File: Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Jules Rabin getting bread ready for the oven at Upland Bakers in 2013

Firing Upland Bakers' oven is a huge task. It takes more than five hours and almost a cord of wood, plus constant feeding and adjustment, to reach the right temperature. Then the ashes must be raked and the oven floor cleaned to ready it for the bread, which bakes in the intense residual heat.

For close to a decade now, the oven has stood cold in the old bakehouse behind the Rabins' Hollister Hill home, gathering dust on the stacked stone face from which wooden bread peels still hang. The massive industrial mixer and a grain mill sit quietly nearby, among boxes of old books and a pair of bicycles.

Jules apologized for the clutter when he recently showed a reporter the oven. Seeing it out of use makes him a little sad. "It was a good instrument, a noble implement," he said. "It's standing well."

He admitted that he is somewhat ambivalent about his legacy. "I honor bread and honor our lives as bakers, but I think it's rather a lowly thing to be known for," he said. Nevertheless, he added, "In our commercial society, in our mendacious society, to be occupied with bread is to be close to what is intrinsically good."

Reflecting on his youthful desire for an "intellectual life," Jules said he would prefer to be recognized for his writing, though he admitted he has published little beyond some essays and many letters to the editor. He still writes almost daily in the morning, typing emails to friends and family and drafting essays. "In the afternoon, I go into decline," he said wryly.

Until recently, Jules also invested time into crafting letters to politicians, including 14 or 15 to President Joe Biden since last October. (He's lost count.) Helen said her husband's spark has been dimmed somewhat by the summer's heat and humidity, which he tolerates less well than in the past.

Jules still finds pleasure in the couple's noontime meal, their main repast of the day, which they enjoy at their round oak table by the picture window with a view of ruby-throated hummingbirds bickering around a feeder and rolling hills in the distance. During the summer, the Rabins might set a table on the small deck overlooking their vegetable garden, as they did recently for a simple but good meal of pesto pasta and homegrown salad. The garden has been scaled back by half since Jules decided, at age 99, to "resign" from garden duty, as Helen put it.

Just this year, he gave up splitting five to six cords of heating wood with a hydraulic splitter, though he will stack the same quantity neatly in the garage. With Helen's help, he still makes about 35 quarts of applesauce from the fruit of their trees and turns garden cucumbers into "real Jewish half sour pickles."

And Jules continues to mow the homestead's acre or so of grass. "I ride like a prince on that tiny riding mower," he said.

He still appreciates "a good intellectual sally" through articles he reads in the New York or London Review of Books, and he revels in composing the small vases of cultivated blooms, grasses and wildflowers dotted about the house. Jules lamented that his powerful hearing aids distort sound such that he can no longer listen to his wife's piano playing or chamber music, but Nessa said her father was delighted at a recent opera performance by how the music animated the body of the conductor.

Jules draws energy from human interaction. During a recent Bread and Puppet show, Nessa and her father ran into a group of young performers moving between stages during a break. She suggested they get out of the way, but Jules protested, "'No, Nessa, no. I need to talk to them,'" she recounted.

In an unpublished essay titled "On Ascending to 100," Jules examined the losses of age and the reasons life is still worth living. "Ecstasy, with its wonderful sheerness, is gone," he wrote. "Satisfaction and small pleasures remain." When asked what he misses most from his life, Jules answered with typical bluntness: "Grand sex," he said, as chagrin flickered over his wife's face. "If I have any wisdom in my old age, it's that I declare ecstasy is gone. Those peaks are gone. Grand sex. It's transporting."

When a reporter dared press further, referencing a recent article about robust senior sex lives, Jules offered, "Things start to peter out in the nineties. You can use that word, 'peter out,' too," he added mischievously.

Truth and Consequences

click to enlarge

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Jules Rabin at a weekly rally in Montpelier seeking peace in Gaza

Jules not only believes in speaking his truth, he often can't hide his deepest feelings. Gainza, his longtime activist friend, recalled a meeting about a decade ago with then-U.S. representative Peter Welch's chief of staff about Israel and Palestine. Jules started to describe how terrible he felt as a Jew about the way Israel was treating Palestinians, but his intense emotions tripped him up. "He tried several times to start again, but he couldn't stop crying," Gainza said.

Eventually, Jules excused himself and left the room. Gainza followed to make sure he was OK. "He turned to me with tears running down his face," Gainza recalled, and apologized for letting down those he was trying to defend.

The current crisis in Gaza feels personal for Jules as a Jew, and he believes the U.S. is complicit. During a reporter's second visit with the couple at their house, Helen reminded her husband that he initially supported the concept of a homeland for the Jewish people. He agreed, though he qualified, "not for myself." Jules recognized that through the first half of the 20th century, "there were great numbers of Jews who didn't just want it, but they needed it. They were done with Europe, and they felt that they would be secure in a land of their own."

Gradually, however, Jules said he came to see the oppression of Palestinians as an unacceptable price to pay. "I think of Gaza every day. It's intolerable to think of what's going on in Gaza as we sit here smug and in plenty," he said. "I feel ... I feel ... I feel..." He paused to gather himself and clear a sob from his throat. "I feel enough to make me cry."

Despite being lauded as a lifelong activist, Jules feels he has not lived up to that standard. "It's only sporadically and now towards the end of my life where I've acquired, I think, a steady morality," he said.

Some of his friends note the futility of vigils, protests and letters to effect change. Nonetheless, Jules said he'll keep speaking out as long as he can. "It's a moral imperative," he said. "I don't expect my words to have consequences. I still hope they will."

Correction, August 12, 2024: An earlier version of this story inaccurately described Jules Rabin's military service. He was on active duty, but was not deployed overseas.

Help us pay for in-depth stories like this one by becoming a Seven Days Super Reader.

The original print version of this article was headlined "A Baker's 100 | Marshfield's Jules Rabin celebrates a century of intellectual curiosity, trailblazing bread and standing up for peace"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

Tags: This Old State, Jules Rabin, Upland Bakers, Marshfield, bread, activism, Video

About The Author

Melissa Pasanen

Bio:

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

Melissa Pasanen is a food writer for Seven Days. She is an award-winning cookbook author and journalist who has covered food and agriculture in Vermont for 20 years.

More By This Author

Latest in Category

Speaking of...

-

'Returning to Haifa' Links the Holocaust and Nakba Tragedies

Aug 7, 2024 -

Q&A: As Emoji Nightmare, Cambridge Resident Justin Marsh Brings Drag to Rural Towns

Jul 17, 2024 -

Video: Cambridge Resident Justin Marsh Brings Drag Queens to Rural Towns as Emoji Nightmare

Jul 11, 2024 -

A Local Veteran Discusses Lessons Learned From War-Gaming a Second Trump Presidency

May 15, 2024 -

Backstory: One Reporter Returned From Vacation to a Flooded Home

Dec 27, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: