Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

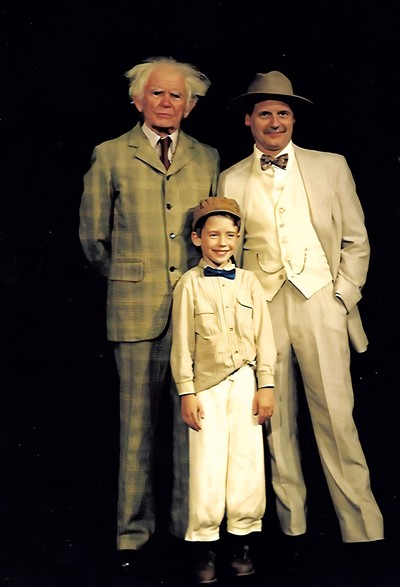

At 99, Bill Blachly Looks Back on 40 Years of Unadilla Theatre

Published July 12, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated July 19, 2023 at 9:56 a.m.

If you didn't know Bill Blachly was the founder and host of Unadilla Theatre in Marshfield, you might mistake him for a member of the cast.

At 99, with a free-range head of white hair and an arresting gaze, he peers out over the theater's remote hill-farm home like a Shakespearean elder. He could be Prospero from The Tempest, preparing to summon a storm — but then he climbs behind the wheel of a tractor to tend to his cattle and sheep. He could be a disillusioned King Lear, lamenting the betrayals of his heirs — but then there they are, gathered merrily in the cozy kitchen of the farmhouse he shares with his partner, Ann O'Brien. Or perhaps the figure he cuts is from Chekhov — world-weary Uncle Vanya, say, pondering his mortality and secretly wishing you hadn't dropped by.

And perhaps Blachly has absorbed a bit of each of these characters, who are among the dozens from the canon of classic and modern dramas that he and O'Brien have produced for 40 years deep in rural Vermont. Their Unadilla Theatre is the theatrical equivalent of a secret swimming hole.

"Unadilla: Find It If You Can," quips Ann's youngest son, John O'Brien, a Tunbridge sheep farmer, filmmaker and state legislator.

Since 1983, thousands of theatergoers have found Unadilla, the place where Blachly has played the real-life role of gentleman farmer while living out his passion for theater. Here he has raised livestock, vegetables, children — and the curtain on about 180 productions. By his count, that's 21 Gilbert and Sullivans, 10 Shakespeares, 10 Chekhovs, six Fugards, six Shaws, three Ibsens, and 130 others.

"It's just been such a part of our life," Ann O'Brien said. "I can never separate the pieces of it all."

This makes Blachly an elder in the generation of urban émigrés who sought a simpler, more grounded life in the countryside during the back-to-the-land movement of the 1960s and '70s. He's also a member in good standing of the counterculture cohort that made something not just crunchy but artful out of rugged Vermont terrain.

He has a decade on Bread and Puppet Theater founder Peter Schumann, who is 89, but the two artists have a lot more than wild, white hair in common. In both cases, longevity and its natural counterpart, succession, have raised questions about the future and sustainability of the cultural landmarks they have created. While patrons of both theaters would be forgiven for thinking the energetic impresarios are decades younger, admiration for what they have achieved brings a bittersweet note to each new season.

Unadilla will stage three shows this summer in its two rustic theaters: A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Pirates of Penzance, and the opera Mozart and Salieri. Uncle Vanya, the play that inaugurated Unadilla in 1983, had been scheduled but was abruptly canceled last week.

Blachly said he doesn't know whether another season will follow this one. He could bow out, of course, and pass the mantle, but that doesn't seem to be much on his mind. "I suppose you could conceive of something like that," he said. "I haven't."

Instead, on a drizzly afternoon last month, he sat in a wingback chair in his book-filled study and discussed the past — how a dyslexic flatlander came to champion live theater in Vermont for more than four decades. And he marveled at how Unadilla has drawn audiences and the cadre of volunteers who, year after year, make its productions possible.

"I'm absolutely amazed," he said, gesturing out the windows of the house and toward the two barn theaters where Midsummer and Pirates were in rehearsals. "These people, the amount of time they put in is staggering ... I think there's a hunger out there to do things like this."

Jersey Boy

Blachly grew up in Montclair, N.J., close enough to Broadway to see shows there as a youth. His struggles in school made theater all the more appealing.

"I couldn't read anything until I was in seventh grade, and I couldn't do math," he said now. "But the school had a good drama department — I guess that's what got me started."

After serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II, Blachly attended Oberlin College in Ohio. After graduation, he ran the drama program at his old high school; studied progressive education at Vermont's Putney School, where he earned a master's degree; and became a college administrator. At Putney, he met his future wife Alice Clifford, an ardent theater fan who worked in the office. Alice remembers Blachly quoting lines from Gilbert and Sullivan shows. "That's some of the wittiest stuff there is," she said. "And I love to laugh."

Blachly's career led him to Brandeis University in Massachusetts, where the job-related stress became overwhelming. When his doctor prescribed a different line of work, "I gave up the whole thing," he said.

Blachly had good intel that Vermont might be the cure. As a boy, he had attended a summer camp near Wilmington, and as a young professional he had served a stint in the administration of Goddard College. But the clearest sign came from his younger sister, Barbara, who owned a broken-down farm in Cabot that Blachly had helped her restore. On a visit there in 1956, he found another decaying farm in nearby Marshfield. For $3,000, he bought the 300-acre place — fire-damaged house, dilapidated barns and all.

Blachly had some work to do to get his farm functioning, but his daughter, Ellie, said a pioneering spirit runs in the family. Blachly's father, Louis, was one of eight sons raised by a single mother after her banker husband was gunned down by robbers in Delta, Colo., in 1893. The Blachly boys knew hard times and passed along an ethic of resourcefulness that shows up strongly in her father, in her view. "My father absolutely grew up with all these stories," she said. "These things live on ... It becomes a part of you and how you think of yourself."

Blachly credits some experiential education, as well. "I bought some cows. That'll teach you very quickly," he said. "Our motto was 'Make do. Use it up. Do it yourself' and all those things."

He milked a herd of about a dozen cows for a decade or so while Alice worked a job off the farm. They had two children, Tom and Ellie. "Well, it wasn't very easy. We just took a chance," Alice said. "That's the way Bill is. He's a risk-taker. I'm not a risk-taker. So that made life exciting."

When new dairy regulations in 1965 compelled Blachly and many small-farm operators to get out of the business, he traded cows for sheep and patched together a living. He served in the Statehouse — the first Democratic rep from Calais — and later worked in the tax department despite being, in his words, "the most improbable sort of person" for the job.

Throughout these efforts to strengthen his family's anchorage in Vermont, Blachly found ways to nurture his love of theater. He directed Tom's school plays and, in the early to mid-1970s, led the successful effort to restore the defunct Barre Opera House. Drawing inspiration from Stratford, Ontario, a bygone industrial hub that had built a world-class theater festival, Blachly invited its founder, Tom Patterson, to help him make the case for a performing arts center in the Granite City.

"If it wasn't for him, I don't know if that thing would be there," Tom Blachly said of his father. "He just worked and worked and worked, and finally it did open." But the new resident company, the Barre Players, had their own ideas about how the shows would go on. "The first thing they did was fire me," Bill Blachly said.

In the meantime, he and Alice had joined a group effort to revive the Plainfield Little Theatre. The troupe usually operated out of the Plainfield Town Hall Opera House, but rehearsals were sometimes held in the Blachlys' Marshfield barn. During the run-up to a production of Uncle Vanya in 1983, it dawned on Blachly that it would be simpler to just stage the show in his barn. The cast was against it, he recalled, but followed his lead.

The way Ellie tells the Unadilla genesis story, it began about a week before opening night and included most of the family. She took charge of the costumes. Her sister-in-law Tina Bielenberg created an advertising poster. There was no stage set, so her father built furniture "so we'd have something to sit on." There was no audience seating either, so Ellie's husband, Carl Bielenberg, constructed a set of seats.

Then, a few hours before opening night, Blachly decided the sight lines were all wrong. "It was my father's dream to have raked seating," Ellie said, referring to an incline of seats up from the stage. "What he wanted was to have an actual theater." Fortunately, Bielenberg had built the seats as a single set of bleachers, which meant that the whole unit could be tipped forward by digging into the dirt floor at the front. "That happened the afternoon before the show opened," she added. "It was extremely dramatic."

The only thing left to do was wait. "I just remember us all standing there, about quarter of eight, in our costumes, of course, staring out the milk house windows and seeing a pair of headlights and saying, 'By God, somebody's come out' ... and then a few more," Ellie recalled. By showtime, the theater was filled, as it was for two additional performances.

They christened the new theater Unadilla, after a manufacturer's name stenciled on the barn rafters. That first show became a piece of Blachly family lore, in part because the cast that night included not just Ellie but Tom and Alice, though she and Bill were divorced by then.

Before the decision to cancel Uncle Vanya last week, Alice was preparing to reprise her role as the nurse Marina, at age 96.

"She was a very important foot soldier and really poured herself into the place," Ellie said of her mother.

Starry, Starry Nights

Patrons in the early years may remember Blachly grandchildren running the concessions stand — homemade baked goods were a favorite — or waiting tables in the simple restaurant where, for a time, the family served home-cooked meals. The restaurant is gone, but otherwise the Unadilla experience is largely unchanged from that first opening night.

An arriving theatergoer turns onto the property near the Calais line to find a cluster of weathered gray barns set off from a white farmhouse. Cattle keep watch on the scene, and a sheep's baa may add to the hubbub. The "lobby" is an outdoor area through a hedgerow, where many patrons picnic al fresco. The main theater, the Unadilla, is a curious-looking Quonset hut with the entrance and concessions window set underneath its arch, creating space to mill around, get out of the rain and peruse the inventory of used books often for sale there.

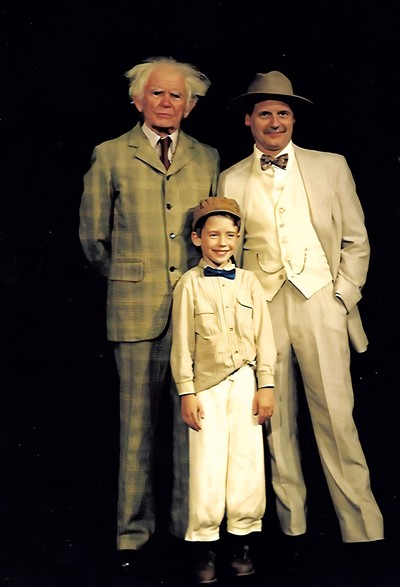

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Unadilla Theater

- Bill Blachly (left) with his son Tom and grandson Adam in a production of Our Town in the early 2000s

The Festival Theatre, a 2011 construction, is a more conventional-looking metal-roofed barn.

Even if Blachly and O'Brien, 93, don't greet patrons themselves, being on their property preshow feels more like social gathering than a night at the theater. "It's definitely a living room," said Calais resident Olivia Gay, who has been attending shows since Unadilla began. "Bill has this big personality, this warmth, this connection with lots of people. He loves people. Ann, too ... Unadilla is an extension of their personalities."

Loyal patron Rick Winston said he gets a kick out of sharing the Unadilla experience with newcomers, especially out-of-towners. "People ask, 'What is this place? I can't believe it,'" he said. And on a pleasant summer evening, the setting offers its own spectacle. "You can always count on just a few people who are standing there, looking down into the valley and enjoying the view," he said.

Those simple charms extend inside the Unadilla theater, with its slightly makeshift look. Wood floors, bench seats, a hanging Tiffany lamp and a worn rug running down the center aisle lend the space a homey feel. Gay, who used to act with Unadilla, said the close proximity of actors and audience in both theaters creates a sense of intimacy. The likelihood that players and patrons know one another as neighbors amplifies that sense, reinforcing the community theater essence of shows. Even a season that has been announced for months retains a sense of spontaneity, as if someone in the neighborhood just proposed putting on a show and invited everyone to play along.

"There's this seamlessness between community life and theater life," Gay said. With Ellie's hand-sewn costumes and set pieces recycled season after season, Unadilla's DIY production values underpromise while the productions themselves often overdeliver.

Sometimes the theater's natural setting actually boosts the production values. A cricket once began chirping, as if on cue, in a production of Uncle Vanya. Gay prepared for her role in Brian Friel's Dancing at Lughnasa by gathering her character's basket of blackberries just outside the theater — doing a little character study while also saving the production a few bucks. And a production of Shakespeare's The Tempest in a barn theater on a stormy summer night heightens a sense of immersion in the play.

Casting Wide

While the unpretentious community theater ethos remains, Blachly has persistently pursued new ways to produce quality work with modest resources.

Large-cast shows, such as the Gilbert and Sullivan and Shakespeare plays that are staples of the Unadilla season, always required local, amateur players. But for a period in the 1980s and into the early '90s, Blachly auditioned professional actors in Boston and New York City. He could offer them on-farm housing in the cabins — "mini-Dillas" — he built for that purpose. This is when Unadilla "really kind of took off," Tom Blachly said. "It brought a level of professionalism ... that kind of rubbed off on the rest of us."

In 1989, while auditioning talent in Boston for an upcoming production, Bill Blachly was closing up his rented audition space when, as he recounted, a "woman came running up and said, 'I hope it's not too late.'" It was professional actress Paula Plum, and she was too late. But she and Blachly crossed the street to the bus terminal and held her audition there. To Blachly's delight, she had memorized much of Happy Days, a Samuel Beckett play that he'd been thinking of staging. Blachly offered her a role on the spot.

Blachly could afford to pay Plum almost nothing, but she nevertheless found Unadilla a productive place "to expand, dare, grow, create," she said. The professional acting pipeline, especially when it passed through Actors' Equity Association contracts, was never a great fit for Unadilla, however. Paying actors Equity scale and performance rights fees for shows not in the public domain proved costly, for one thing. Putting up actors on the farm became too onerous, for another, especially the year when all the actors stayed in the Blachly-O'Brien house. "That was wild," he said.

Ultimately, the deal-breaker was the Equity rule that gave actors the option of leaving a show mid-production if they received a better offer. That piece of kryptonite dropped during a 1990 run of the George Bernard Shaw play Man and Superman. Three actors quit, and, without the luxury of understudies, Blachly had to pull the plug. He returned to using mainly volunteer casts and crews.

Roughly three decades later, Unadilla holds to that model. "We don't have any budget at all for most things," Blachly said.

The laid-back vibe has proved difficult to quantify but impossible to miss. Plum, whose résumé is long with stage, film and television credits, thrived on it during her frequent returns to Unadilla. Despite Blachly's de-emphasis on professional acting, she continued to bring one-woman shows to Marshfield and grew enamored of Unadilla's culture-savvy core audience. "People just love to talk about the theater. People read," she said. "You can start a Robert Frost poem, and someone will finish it."

Zephyr Teachout — a New York politico, law prof, author and special adviser to the New York State Attorney General's Office — became another member of the Unadilla family. She made her Unadilla debut in a 1992 run of Shakespeare's Love's Labour's Lost and continued to return for some summer performances during her college years and beyond.

"I was captivated by every part of that theater," she said. "I still have those lines from Cymbeline ... in my head. 'Arm me audacity from head to foot!'" She called performing with Unadilla "one of the great joys of my life."

Blachly's direction was part of that. Teachout, who played Willie in Happy Days in 2017, offered an illuminating account of Blachly's method. That's method, not Method — as in the psychologically exploratory Stanislavsky Method popular with generations of actors. She remembers rehearsing and then "waiting for the notes and waiting for the notes, and he has four notes total," she said. "And one of them will be, 'Will you pronounce that last word in the sentence ... better?' What I saw was these little adjustments that would make extraordinary differences in the tempo and the feeling of the play."

Blachly would probably be unsurprised by this assessment. "Mostly I don't really direct," he said. "I say, 'Go stand over there'... I just move them around. Sometimes the actors make fun of me ... But I think the Method certainly made actors more self-conscious."

Blachly's minimalist approach doesn't mean he's without strong opinions. Plum learned this the hard way when she signed on to direct a production of Václav Havel's Temptation, a political satire. What Plum calls one of their "knock-down drag-outs" was so unresolvable that Blachly scuttled the show.

"I fired her," Blachly said. "Nowadays I probably wouldn't have done that," he added. "Mostly I keep my big mouth shut."

Blachly has had a "volcanic" temper, according to John O'Brien, who cast and directed his de facto stepfather in the 1996 mockumentary Man With a Plan. He recalled an incident in which Blachly threw cheese — soft cheese, Brie — at his mother. (To be fair, Ann admits to tossing a pan of lukewarm dishwater at Blachly during a spat.)

Alice Blachly remembered an incident or two in which Bill Blachly raised his voice during a rehearsal, although she never found anything mean in it — just a strategy for using a tantrum to get his way, she speculated. In any case, both Alice and Ellie said Blachly has definitely mellowed with age. On the rare occasions when he explodes, "what doesn't drive people away is that he's quick to calm down and either apologize or say, 'I lost my mind there' ... In that way, he's very generous," O'Brien said.

Teachout has been the beneficiary of that generosity as she has grown from bit player to best friends with Blachly and Ann O'Brien. "When I was there as a 20-year-old, their house was kind of sacred. You didn't just tromp in and out," she said. Nowadays, she appreciates the chance to talk "science to poetry to history and then this infinite, infinite catalog of theater that resides in that house" over a "cuppa" — Blachly's slang for morning coffee — or a "glassa," an evening glass of wine. In 2013, she and her 8-month-old son lived in a mini-Dilla while she worked on her book Corruption in America. She remembered Blachly helping show her son "how to bang on pots and pans."

Teachout reserves special praise for O'Brien's "hilarious deadpan delivery," possibly a counterweight to Blachly's mirthful manner. Like Plum, Teachout acknowledges the essential partnership between Blachly and O'Brien that defines Unadilla, even if Blachly is more visible as a director and producer.

"Bill is a chaos machine," Plum said — albeit one with "charm, charisma and capability." O'Brien is the fixer. "She's the heart of that organization."

The Plots Thicken

Blachly's foray into professional casting in the 1980s supported his effort to blend classic theater with more contemporary work on the Unadilla boards. He and O'Brien took to making regular off-season trips to London, as well as to Stratford and the Shaw Festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, to stay up on new plays.

He became especially interested in the work of South African playwright Athol Fugard. In 2005 alone, Unadilla staged two of the author's works, The Island and "Master Harold"...and the Boys, that explore the moral complexities of apartheid. The following season, Unadilla staged My Name Is Rachel Corrie, a 2005 play composed from diary entries and emails written by an American peace activist crushed to death under an Israeli Defense Force armored bulldozer in the Gaza Strip in 2003. Teachout starred in a 2019 staging of Florian Zeller's The Father, which deals with dementia caregiving.

"Just the fact that it happens and where it happens is kind of miraculous." Andrea Serota tweet this

The wide range of plays Blachly has selected over the years has enabled Unadilla to present engaging theater that brings valued culture to the countryside, even when the quality doesn't hit a high mark. Song-and-dance numbers might be a little loose. That Shakespearean verse might not roll off the tongue. And an edgy play might sound a strident note here and there.

Unadilla regular Andrea Serota put it this way: "Even when I wish [the shows] were better in terms of performance, just the fact that it happens and where it happens is kind of miraculous to me."

With characteristic irony, Blachly suggested that responses like Serota's might be evidence that the Unadilla experience writ large is a hedge against dissatisfied patrons. "My theory, maybe it's a theory of necessity, is that you leave Route 14, you drive up an old gravel road, you pull into an old barn, you sit on some relatively uncomfortable seats and you get a good show," he said. "So, reduce your expectations. And then people think, My goodness, that was quite amazing. That was quite a good show."

Self-deprecation aside, to say Unadilla gets more than it pays for is an understatement. Bill Blachly has made the most of what he's had to work with, thanks to what Tom Blachly calls his "intuitive" directing style and good instincts for casting the right people in the right roles. Reviewers for local media have consistently praised Unadilla shows as worth the price of admission (this year, $25 for an adult) and a back-roads trek to the farm.

Perhaps Teachout's insight is right, then, that Blachly's strong presence offstage correlates with strong presence onstage. "He has great confidence in his judgment," she said, "and that confidence is communicated in the plays."

Blachly has also come to show confidence in new directing talent. At this moment in early July, A Midsummer Night's Dream is running in the Festival Theatre under the direction of Jeanne Beckwith, a returning Unadilla director. She holds a doctorate in theater and brought with her to Vermont decades of playwriting and directing experience.

In the Unadilla, The Pirates of Penzance came together under the direction of Erik Kroncke, a professional opera singer who tours nationally and internationally when not at home in Montpelier. Like Beckwith, he has helmed other musical shows in the backwoods of Marshfield.

In place of Uncle Vanya, Kroncke will direct, in collaboration with Pirates music director Mary Jane Austin, the opera Mozart and Salieri as part of a Mozart-themed evening of opera and concert arias over the first two weekends in August. Movie fans may find the opera's libretto by Alexander Pushkin familiar, as it was the inspiration for 1984's Amadeus (after Peter Shaffer's play of the same title). The show will feature tenor Adam Hall and bass Kroncke, with Austin accompanying on piano.

Curtain Calls

The drive and perseverance it has required to sustain Unadilla, to literally build and maintain its structures and grounds, is perhaps Blachly's greatest contribution to the theater. It has certainly been his most visible. At the end of the day, as well as in the beginning and the middle, Blachly is a man of action.

"Everybody remarks on Bill's energy, which we're all in awe of," John O'Brien said. He recalled a time when Blachly took "a flying leap" out of a pickup truck — in his nineties — while the two of them were moving sheep. At age 78, Blachly had a brush hog accident. Pinned beneath the upside-down machine with its blades spinning, he escaped injury only because the lever for the hydraulic loading bucket jammed into his ribs. The bucket lifted, pushing the tractor off the ground and rolling it off him.

"He managed to somehow crawl back to the house," Ellie Blachly said. "He had four cracked ribs, and that's all. Pretty much everyone concluded, 'You're safer running the theater.'"

"Bill never stops," Plum said. "I'd wake up in the morning, and Bill would be out there on the backhoe, plowing the fields, wrangling the cows back into the pasture, building something. He's a bit manic. He's restless and indefatigable."

Blachly has rolled with the challenges over the years, including the COVID-19 pandemic, which closed Unadilla down for the 2020 season. More recently, he lamented the difficulty of coordinating cast and crew schedules in producing a show. That's what doomed this year's Uncle Vanya.

Amid all that can go wrong in producing live theater, however, he has made an "astonishing" observation about what hasn't bedeviled Unadilla: "We can do an entire season of maybe three, four, five shows with maybe 100 people onstage, and nobody gets sick," he said. "What is going on? Something in the air? ... Theater must be conducive to health."

While he hasn't made any decisions about next season, he can be drawn into thinking about who might succeed him. "You've got to face it: At 99, you're not looking at the next decade," he said. "But I've really cultivated some other directors, like Alex [Brown] and Monica [Callan]." He said Brown, who also reviews plays for Seven Days, was his first choice to direct Uncle Vanya. When he couldn't offer her the rehearsal time she needed, he took the gig himself.

That's a noteworthy development to Tom. "My dad's generally cut back a lot," he said. "He used to direct a lot of the shows there. In more recent years, he's basically hired directors." Blachly has lightened his workload in other ways, too. He sold his herd of cattle and sheep last fall. For various reasons, the person who bought them didn't want them all, so two of the cows and a bull, along with eight sheep, returned to the farm.

To keep the theaters running, he has had good help for almost a decade. Lori Stratton, an environmental toxicologist, began assisting with stage lighting in 2014, and now Blachly calls her "the all-purpose stage manager for most of the shows and the reason that we are still here."

Just then, Stratton ducked into his study to talk about lighting malfunctions and a conspicuous smell in one of the theaters. (Probably a dead bird, she reported later.) "Every company should have a Lori," Blachly said. "She does everything. She drives to Amherst to pick up the costumes that we rent. She cleans the theater. She plants the garden."

This season she has a local high school student running the lighting and sound for one show, since she can't be in two places at once. While she's happy for the help, it pains her a bit to work with the Pirates cast but be unable to see the show while in charge of Midsummer tech in the Festival Theatre. It's a necessary sacrifice. "I get a real thrill out of seeing a play evolve over time," she said. "I want to see this theater continue. People love it. And people are very nostalgic about Unadilla. They like coming back."

But will they have something to come back to next summer? Not even those in the Unadilla inner circle are placing bets. The question is hardly new. "Every season is the last season," Teachout said. "And in January I get a phone call. 'What are you doing this summer?'"

Ellie Blachly also knows the drill: "This has been the last season of the theater for at least 15 years," she noted.

All that anyone can say for sure is that Bill Blachly and Ann O'Brien have championed quality theater in a pastoral setting that can make a play seem as if it starts at the turn onto Blachly Road. Tom calls it a Brigadoon, after the musical about two New Yorkers who stumble into a Scottish village that doesn't appear on any maps. "There is a little touch of magic about the place," his sister, Ellie, said.

To sit and talk theater with Blachly is to trace some of that magic back to its source. His eyes light up when the subject returns to Uncle Vanya. "Every character has some ironic twist, and that's what Chekhov is about," he said, reaching for a script of the play. "This is the genius of the guy ... These characters all set out in life as young people to be something totally different." He thumbed to Sonya's final monologue in the play and read aloud: "What can we do? We must live out our lives. Yes, we shall live, Uncle Vanya. We shall live all through the endless procession of days ahead of us, and through the long evenings."

By the end of Sonya's monologue, Vanya has tears in his eyes. But as he tossed his script on the coffee table, Blachly was smiling.

The Pirates of Penzance, by Gilbert and Sullivan, directed by Erik Kroncke, produced by Unadilla Theatre, and A Midsummer Night's Dream, by William Shakespeare, directed by Jeanne Beckwith, produced by Festival Theatre: Thursday, July 13, through Saturday, July 15, 7:30 p.m.; and (Pirates only) Sunday, July 16, 2:30 p.m., at Unadilla Theatre in Marshfield.

Mozart and Salieri, by Alexander Pushkin, and select Mozart works, directed by Mary Jane Austin, produced by Unadilla Theatre: Thursdays and Saturdays, August 3, 5, 10 and 12, 7:30 p.m., at Unadilla Theatre in Marshfield.

As of press time, Unadilla Theatre had not canceled any performances following the recent flooding throughout Vermont. Call 456-8968 or email [email protected] for the most up-to-date information.

The original print version of this article was headlined "Well Played | At 99, Bill Blachly looks back on 40 years of Unadilla Theatre"

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Author

Erik Esckilsen

Bio:

Erik Esckilsen is a freelance writer and Champlain College professor who lives in Burlington.

Erik Esckilsen is a freelance writer and Champlain College professor who lives in Burlington.

More By This Author

Latest in Theater

Related Locations

-

Unadilla Theatre

- 501 Blachly Rd., Marshfield Barre/Montpelier VT 05658

- 44.37692;-72.39672

-

802-456-8968

802-456-8968

- www.unadilla.org

Related Stories

Speaking of...

-

'Returning to Haifa' Links the Holocaust and Nakba Tragedies

Aug 7, 2024 -

A Tour of Montpelier Arts Businesses and Organizations Affected by the Flood

Jul 19, 2023 -

From Shakespeare to the Beatles, Vermont’s Community Theaters Offer a Variety of Summer Fun

May 17, 2023 -

Unadilla Theatre Stages an Opera Favorite

Aug 3, 2022 - More »

find, follow, fan us: